The Russian Revolution of 1917 was a transformative event that dismantled the centuries-old Tsarist autocracy and set the stage for the rise of the Soviet Union, the world’s first socialist state. The revolution was fueled by a confluence of factors including widespread discontent with Tsar Nicholas II’s regime, severe economic hardships, and the enormous toll of World War I. The February Revolution, driven by mass protests and food shortages, forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate and led to the establishment of a Provisional Government. However, the Provisional Government’s inability to address critical issues like land reform and continued war efforts created a vacuum of power that the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were poised to exploit.

In October 1917, the Bolsheviks seized power in a dramatic coup, marking the beginning of a new era in Russian and global history. This revolutionary change not only ended the Romanov dynasty but also inaugurated a socialist regime that sought to radically transform Russian society. The establishment of the Soviet Union would go on to influence global politics, inspiring communist movements worldwide and setting the stage for the ideological conflicts of the 20th century. This article delves into the pivotal events of 1917, exploring the causes, key developments, and enduring impact of the Russian Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union.

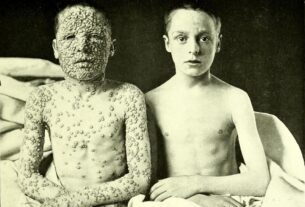

(picryl.com)

Background and Causes

(Autocratic Rule and Political Repression)

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was deeply rooted in the long-standing autocratic rule of Tsar Nicholas II, whose reign epitomized the rigidity and oppressive nature of the Romanov dynasty. Nicholas II’s refusal to relinquish any of his absolute power and his resistance to implementing meaningful reforms alienated not only the working class and peasantry but also segments of the nobility and intelligentsia. His policies were characterized by a staunch commitment to maintaining autocracy, which included the brutal suppression of any political opposition. The use of secret police, particularly the Okhrana, to monitor, arrest, and exile dissidents created a climate of fear and resentment across Russia.

The discontent with Tsarist rule was not a sudden development but rather the culmination of decades of dissatisfaction. The 1905 Revolution, which had been brutally suppressed, had already exposed the weaknesses of the regime. Although the establishment of the Duma, a legislative assembly, was a concession to the demands for reform, Nicholas II’s consistent refusal to share power rendered it ineffective. The Tsar dissolved the Duma whenever it challenged his authority, revealing the limitations of these reforms and further alienating the population. This political repression contributed significantly to the revolutionary fervor that would later culminate in 1917.

(Agrarian Discontent and Peasant Poverty)

At the core of Russia’s societal issues was its predominantly agrarian economy, which left the majority of the population—about 80%—living in rural areas under conditions reminiscent of feudalism. The Emancipation Reform of 1861, which was supposed to free the serfs, did little to alleviate their suffering. The land allocated to the peasants was often insufficient for subsistence and came with heavy redemption payments, trapping them in a cycle of debt and poverty. This system created a deep sense of frustration and resentment toward the ruling class and landowners, fueling the desire for radical change.

Peasant discontent was further exacerbated by the continued exploitation and harsh living conditions they endured. The rural population, burdened by taxes and oppressive labor obligations, saw little hope for improvement under the existing system. The Tsarist regime’s failure to address the land issue effectively led to growing unrest in the countryside. As the 20th century progressed, the demand for land reform became increasingly urgent, setting the stage for the revolutionary events that would follow. The peasants, who had long been marginalized and oppressed, were now poised to play a crucial role in the upheaval that would reshape Russia.

(Urbanization and Industrial Worker Discontent)

While Russia remained largely agrarian, the early 20th century saw a limited but significant urbanization that led to the emergence of an industrial working class. Cities like St. Petersburg and Moscow became centers of industry, where a new class of industrial workers faced harsh conditions. These workers were subjected to long hours, low wages, and virtually no political rights, creating a volatile environment ripe for revolutionary sentiment. The concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a small elite, often foreign capitalists, further fueled nationalistic and anti-capitalist sentiments among the urban proletariat.

The plight of industrial workers was a stark contrast to the wealth and privilege of the Russian elite. Strikes and protests were common, but they were brutally suppressed by the Tsarist regime, which only served to radicalize the workers further. The absence of labor rights and the government’s unwillingness to address the grievances of the working class led to a growing sense of alienation and anger. By 1917, the industrial working class had become a critical force in the revolutionary movement, their demands for better working conditions and political representation resonating with the broader discontent across Russian society.

(Impact of World War I)

World War I acted as a catalyst that accelerated the disintegration of the Tsarist regime and brought the underlying social and economic tensions in Russia to a breaking point. Russia’s involvement in the war was disastrous from the outset. The military, poorly equipped and inadequately led, suffered catastrophic defeats such as the Battle of Tannenberg. These military failures not only decimated the Russian army but also severely undermined the morale of both soldiers and civilians. The war effort placed an immense strain on the already struggling economy, leading to severe food shortages, skyrocketing inflation, and a breakdown in transportation networks.

The social fabric of Russia was further torn apart by the massive loss of life during the war, with millions of soldiers killed or wounded. The government’s inability to provide for the needs of the population during this time of crisis led to widespread dissatisfaction and disillusionment. Soldiers, many of whom were peasants in uniform, became increasingly mutinous, deserting in large numbers as they saw no reason to continue fighting for a regime that seemed incapable of ensuring their survival. The war, initially intended to unite the nation, instead highlighted the deep divisions within Russian society and contributed significantly to the revolutionary fervor that would soon explode.

(Tsar Nicholas II’s Leadership and the Role of the Tsarina)

Tsar Nicholas II’s decision to take personal command of the Russian army in 1915, in an attempt to bolster the war effort, proved to be a disastrous move that further isolated him from the realities of the home front. By leaving the governance of Russia in the hands of the Tsarina Alexandra, Nicholas unwittingly exacerbated the growing discontent. Alexandra’s reliance on the mystic Rasputin for guidance and her German heritage made her deeply unpopular among both the Russian populace and the political elite. Rasputin’s influence over the Tsarina was widely viewed as a symbol of the corruption and incompetence of the imperial government.

The perception of a corrupt and ineffective leadership, both on the front lines and in the capital, eroded any remaining loyalty to the Romanovs. The Tsarina’s administration was seen as out of touch with the needs of the people, and her decisions, often influenced by Rasputin, were met with widespread disdain. This further alienated the Russian people and contributed to the erosion of the monarchy’s authority. By early 1917, the situation in Russia had deteriorated to the point where revolutionary change seemed not only possible but inevitable, setting the stage for the February Revolution and the eventual downfall of the Romanov dynasty.

The February Revolution

(The Immediate Catalysts of the February Revolution)

The February Revolution of 1917 was the result of mounting discontent that had been simmering for years, but the immediate catalysts were the acute food shortages and economic hardships that gripped Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) during the harsh winter of 1916-1917. The war effort had severely strained Russia’s fragile economy, leading to breakdowns in transportation and distribution networks. Breadlines became increasingly common, and the lack of basic necessities such as food and fuel caused widespread frustration and anger among the population. The extreme cold of the winter only exacerbated these issues, creating a severe crisis in the capital that pushed the populace to the brink.

The tipping point came on February 23, 1917 (Julian calendar; March 8 in the Gregorian calendar), during the observance of International Women’s Day. On this day, women workers in Petrograd, fed up with the bread shortages, took to the streets in protest. What began as a peaceful demonstration quickly grew as workers from various factories, including men, joined the march. The protests expanded beyond demands for bread to include calls for peace and an end to Russia’s involvement in World War I. This spontaneous uprising soon escalated into a full-scale revolt, with strikes and demonstrations spreading rapidly across the city, signaling the start of a revolution that would bring down the Tsarist regime.

(The Collapse of Tsarist Authority)

As the protests in Petrograd grew, the Tsarist government’s ability to maintain control quickly deteriorated. Soldiers, many of whom were already disillusioned by the war and suffering similar hardships as the civilians, began to mutiny. Initially, the Tsar’s troops were ordered to suppress the demonstrators, but many soldiers, sympathizing with the protesters and sharing their grievances, refused to fire on the crowds. Instead, they defected to the side of the protesters, significantly weakening the Tsar’s authority and accelerating the collapse of the government.

Nicholas II, who was away at the front with the army, was out of touch with the rapidly unfolding events in Petrograd. His ministers, overwhelmed by the scale of the unrest, offered conflicting advice, while the Tsarina Alexandra, left in charge in the capital, was increasingly isolated and distrusted. The Duma, Russia’s legislative assembly, recognizing the gravity of the situation, urged the Tsar to abdicate in an attempt to prevent further bloodshed and maintain some semblance of order. On March 2, 1917 (Julian calendar; March 15, Gregorian calendar), under immense pressure and with his support crumbling, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated the throne. His abdication marked the end of over three centuries of Romanov rule and the collapse of the Russian autocracy, as Grand Duke Michael, Nicholas’s brother, also refused the crown, effectively ending the monarchy.

(The Establishment of the Provisional Government)

In the power vacuum left by the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, a Provisional Government was quickly formed to lead the country through this period of transition. The Provisional Government was composed mainly of liberal politicians and moderate socialists, who aimed to stabilize the nation and lay the groundwork for a democratic system. They sought to address the immediate needs of the Russian people while continuing Russia’s involvement in World War I, hoping to secure a favorable peace. However, this decision was deeply unpopular among the war-weary population, who were desperate for an end to the conflict that had brought so much suffering.

From the outset, the Provisional Government faced significant challenges. It struggled to assert its authority in a country that was increasingly disillusioned with the existing power structures. At the same time, the Petrograd Soviet, a council of workers’ and soldiers’ deputies, emerged as a powerful rival to the Provisional Government. Representing the interests of the urban working class and the military, the Soviet quickly gained influence, particularly among those who felt that the Provisional Government was not addressing their immediate needs. This dual power structure created an environment of instability and political tension that would eventually lead to further revolutionary developments, culminating in the October Revolution later that year.

(The Dual Power Structure and Rising Tensions)

The February Revolution, while successful in toppling the Tsarist regime, also exposed the deep divisions within Russian society and the complexities of governing a nation in turmoil. The Provisional Government, despite its intentions to steer Russia towards democracy, found itself increasingly at odds with the Petrograd Soviet. The Soviet, which had the support of the workers and soldiers, began to assert more control over key aspects of governance, particularly in the areas of military and economic policy. This created a dual power structure where both the Provisional Government and the Soviet claimed legitimacy, leading to a situation of ongoing instability.

The tensions between the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet were further exacerbated by the government’s decision to continue the war effort. This decision was deeply unpopular, especially among the soldiers and workers who were bearing the brunt of the war’s hardships. The inability of the Provisional Government to deliver on its promises of peace, land reform, and improved working conditions led to growing dissatisfaction among the population. As the months passed, the revolutionary fervor that had brought down the Tsar began to turn against the Provisional Government itself, setting the stage for the Bolsheviks’ rise to power in the October Revolution.

The October Revolution

(The Provisional Government’s Struggles and Widespread Discontent)

The October Revolution of 1917 was the inevitable result of mounting tensions and dissatisfaction that had been brewing since the February Revolution. The Provisional Government, which had taken over after the fall of the Tsar, quickly found itself unable to address the critical issues facing Russia. One of its most controversial decisions was the continuation of Russia’s involvement in World War I. Despite widespread opposition to the war, the government insisted on continuing the fight, hoping to secure a favorable peace. This decision alienated a vast portion of the population, including soldiers and civilians who were weary of the immense loss of life, economic collapse, and ongoing hardships caused by the conflict.

The government’s failure to address the land question further eroded its support. The majority of Russia’s population consisted of peasants who were desperate for land reform. They had long been promised redistribution of land, but the Provisional Government’s inability or unwillingness to fulfill these promises led to increasing unrest in the countryside. Peasants began to take matters into their own hands, seizing land from landowners in defiance of the authorities. Meanwhile, workers in urban areas grew increasingly disillusioned as the government failed to improve their living and working conditions, fueling further resentment and setting the stage for the Bolsheviks to gain influence.

(The Rise of the Bolsheviks and Lenin’s Leadership)

Amidst the growing turmoil, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, began to emerge as a powerful force advocating for radical change. Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917, which was facilitated by the Germans who sought to destabilize Russia further, marked a turning point in the revolution. Upon his arrival, Lenin immediately set about galvanizing the Bolshevik Party with his April Theses, which called for the transfer of power to the Soviets (councils of workers and soldiers’ deputies), an end to the war, and the redistribution of land. His slogans of “peace, land, and bread” resonated deeply with a population exhausted by war, poverty, and political instability, significantly boosting the Bolsheviks’ appeal.

Throughout the summer and early autumn of 1917, the Bolsheviks capitalized on the growing discontent among the masses. They gained control of key Soviets, including the influential Petrograd Soviet, and worked to build a broad base of support among workers, soldiers, and peasants. The Provisional Government, under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky, increasingly found itself isolated and incapable of addressing the country’s crises. The Kornilov Affair in August 1917, where General Lavr Kornilov attempted a coup against the government, only served to weaken Kerensky further and bolster the Bolsheviks, who were seen as defenders of the revolution.

(The October Insurrection and Seizure of Power)

By October 1917, the situation in Russia had reached a critical point. The Bolsheviks, under Lenin’s leadership, were convinced that the time was ripe for a decisive seizure of power. Lenin, who had been advocating for an insurrection, persuaded the Bolshevik Central Committee to act. On the night of October 25-26, 1917 (Julian calendar; November 7-8, Gregorian calendar), the Bolsheviks, supported by the Petrograd Soviet and the Red Guards, launched a well-coordinated insurrection in Petrograd.

The revolution began with the seizure of key strategic points in the city, including bridges, telegraph stations, and railway terminals. By the early hours of October 26, the Bolsheviks had surrounded the Winter Palace, the seat of the Provisional Government. Despite later Soviet propaganda that mythologized the storming of the Winter Palace, the actual event was relatively bloodless, with the poorly defended and demoralized government forces offering little resistance. By the morning, the Provisional Government had been overthrown, and its leaders were arrested, marking the end of the Provisional Government and the beginning of Bolshevik rule.

(The Establishment of Bolshevik Rule and Global Impact)

The success of the October Revolution marked the beginning of a new era in Russian history and the establishment of the world’s first socialist state. On October 26, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets convened, where the Bolsheviks announced the formation of a new government, the Council of People’s Commissars, with Lenin as its head. One of the new government’s first acts was to issue the Decree on Peace, calling for an immediate armistice and negotiations for a just and democratic peace. This was quickly followed by the Decree on Land, which declared the abolition of private property and the redistribution of land to the peasants, addressing one of the key demands of the revolution.

The October Revolution, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, had far-reaching consequences, both in Russia and globally. It led to the creation of the Soviet Union, which would become a major global power and the center of communist ideology. The revolution also inspired similar movements worldwide, leading to the spread of socialism and communism in various countries. However, the revolution also plunged Russia into a brutal civil war and set the stage for decades of authoritarian rule under the Bolsheviks. The new government consolidated its power through a combination of political repression, economic centralization, and state control over all aspects of life, establishing a regime that would shape the course of the 20th century.

The Civil War and Consolidation of Power

(The Russian Civil War: A Divided and Brutal Conflict)

The Bolsheviks’ seizure of power in October 1917 was a monumental shift in Russian history, but it did not end the struggle for control over the vast and diverse country. The immediate aftermath of the October Revolution saw the emergence of intense opposition from various factions, collectively known as the White Army. This coalition included monarchists seeking the restoration of the Tsar, conservatives, liberals, and even some socialist groups opposed to Bolshevik rule. The Russian Civil War, which raged from 1918 to 1922, was marked by extreme violence and profound divisions within Russian society. The White Army’s lack of cohesion and diverse objectives hindered its effectiveness, resulting in a fragmented opposition to the Bolsheviks.

The conflict was not merely a military confrontation but also a societal upheaval. Both sides committed atrocities, with the Bolsheviks employing terror as a tool of control in a campaign known as the Red Terror. This involved widespread executions of perceived enemies, including former Tsarist officials and landlords. The White forces also engaged in brutal repressions, known as the White Terror, targeting Bolshevik sympathizers, Jews, and others. The civil war thus became a period of immense suffering and brutality, exacerbating the existing social and economic turmoil in Russia.

(Bolshevik Strengths and Strategies)

The Red Army’s eventual victory in the civil war was due to several key factors. One significant advantage was their control of central Russia, including major cities like Petrograd and Moscow. This centralization provided the Bolsheviks with access to vital resources and industrial centers, bolstering their capacity to sustain the war effort. The Red Army, led by Leon Trotsky, was more unified and better organized compared to the White Army. Trotsky’s leadership played a crucial role in transforming the Red Army into a disciplined and effective fighting force, employing a mix of ideological fervor and strict military discipline.

The Bolsheviks also utilized former Tsarist officers to provide essential military expertise, despite the coercive methods used to recruit them. Their strategic advantage was further strengthened by the disorganization and infighting within the White movement. The reliance on foreign intervention, which was often poorly coordinated and half-hearted, also undermined the White forces’ efforts. Additionally, the Bolsheviks’ ability to maintain support among the working class and peasantry, despite the hardships of the war, played a crucial role in their eventual victory.

(Economic and Social Reorganization)

In the aftermath of their victory, the Bolsheviks undertook significant measures to consolidate their power and reorganize the economy. One of the key strategies was the implementation of War Communism, which involved the nationalization of industry and the centralization of the economy under state control. This policy included requisitioning grain from peasants to feed the cities and the Red Army, as well as nationalizing all major factories, banks, and other key industries. While these measures were instrumental in sustaining the Bolshevik war effort, they also caused widespread hardship, particularly among the peasantry, who resisted grain requisitioning.

The Bolsheviks also made substantial changes to land policy during and after the civil war. They initially allowed peasants to seize land from the nobility, which helped secure peasant support. However, the subsequent centralization of agricultural production and the eventual collectivization of agriculture under Stalin introduced new complexities and challenges. This policy, while designed to strengthen state control over agriculture, would later lead to devastating consequences for the peasantry but was effective in the short term in consolidating Bolshevik support.

(The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the Formation of the USSR)

The end of the civil war did not immediately bring peace to Russia, but it did mark the beginning of a new political era. In March 1918, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, officially ending Russia’s involvement in World War I. The treaty was highly controversial due to the significant territorial concessions it involved, including the loss of Ukraine, the Baltic states, and parts of Poland and Belarus. Despite the criticism, Lenin argued that these concessions were necessary to preserve the revolution and focus on consolidating power domestically.

The formal establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in December 1922 marked the culmination of the Bolsheviks’ efforts to create a centralized socialist state. The USSR united Russia with several neighboring territories under a single federal government. This new political entity would play a major role in global affairs throughout the 20th century, shaping the course of international relations and ideology. However, the creation of the Soviet Union also set the stage for the authoritarianism and repression that would characterize the Soviet regime under leaders like Stalin, profoundly impacting both Russia and the world.

The Legacy of the Russian Revolution

(Domestic Transformations and Challenges)

The Russian Revolution of 1917 brought about sweeping social and economic changes within Russia. One of the immediate effects was the redistribution of land from the nobility to the peasantry. This move aimed to address the longstanding agrarian issues that had plagued Russia, granting peasants ownership of the land they worked. Initially, this policy was popular among the peasantry, as it promised to rectify historical injustices and improve their living conditions. However, the subsequent implementation of Stalin’s collectivization policies reversed much of this land redistribution, leading to widespread famine and suffering. The shift from individual land ownership to collective farming was intended to increase agricultural efficiency but often resulted in severe economic and human costs.

Another major transformation was the nationalization of industry. The Bolsheviks, committed to building a socialist economy, took control of major industries, banks, and transportation networks. This centralization of economic power under state control aimed to eliminate the exploitation inherent in capitalism and create a more equitable society. However, the realities of implementing such drastic changes in a country that was both largely agrarian and war-torn led to significant challenges. The economy struggled to recover from the disruptions caused by World War I and the civil war, and the centrally planned economy proved to be inefficient and prone to corruption. The struggle to balance rapid industrialization with economic stability marked a significant challenge for the Soviet regime.

(Cultural and Intellectual Control)

The Bolshevik revolution also had a profound impact on cultural and intellectual life in Soviet Russia. The new Soviet government sought to shape the narrative of the revolution and promote socialist realism in art and literature. This cultural policy was intended to align artistic expression with the ideals of socialism, rejecting bourgeois values and promoting the revolutionary ethos. However, this effort to control cultural output led to the suppression of dissenting voices and the repression of intellectual freedom. Artists, writers, and intellectuals were often required to conform to the party line or face persecution, stifling creativity and diversity in the arts.

The state control over cultural and intellectual life was part of a broader effort to build a new Soviet identity. This included the promotion of propaganda that glorified the revolution and its leaders while denouncing the old regime and its supporters. The suppression of alternative viewpoints and the enforcement of ideological conformity were central to the Bolshevik strategy of consolidating power and building a cohesive socialist society. The repression of intellectual and artistic freedoms highlighted the tension between ideological goals and the reality of governance in a revolutionary state.

(Global Influence and the Cold War)

The Russian Revolution had a significant impact on the global stage, inspiring communist movements and revolutionary actions across the world. The success of the Bolsheviks in overthrowing the Tsarist regime offered hope to oppressed and exploited peoples worldwide that a socialist revolution could achieve similar results. This inspiration led to the formation of communist parties in numerous countries and the establishment of socialist states in regions such as China, Cuba, and Eastern Europe. The global spread of communism was a direct consequence of the Russian Revolution’s ideological appeal and its promise of social justice and equality.

The revolution also set the stage for the Cold War, a period defined by ideological conflict between the Soviet Union and the capitalist world, led by the United States. The emergence of the Soviet Union as a global superpower, committed to spreading its socialist ideology, directly challenged the capitalist bloc. This rivalry led to decades of geopolitical tension, proxy wars, and an arms race that brought the world to the brink of nuclear conflict. The Cold War shaped much of 20th-century global politics and had a profound impact on international relations and security.

(Legacy and Contemporary Perspectives)

The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to influence contemporary political movements and debates around the world. While the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the ideas of socialism and communism still play a role in political discourse and activism. The revolution serves as a reminder of the potential for radical change and the complex interplay between ideology, power, and human rights. The impact of the revolution on Russian history, politics, and society remains a powerful force, shaping the country’s identity and its role in the global arena.

In Russia itself, the legacy of the revolution is a subject of ongoing debate. Some view it as a tragic period marked by violence and repression, while others consider it a necessary step in the nation’s development and a source of national pride. The revolution’s impact on Russian culture, politics, and society continues to be felt, influencing the country’s historical narrative and its place in the world. The diverse perspectives on the revolution reflect the enduring significance of this pivotal moment in history and its complex legacy.

Conclusion,

The Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent rise of the Soviet Union marked a seismic shift in the course of Russian and global history. The fall of the Romanov dynasty and the establishment of a socialist government set in motion profound changes that would reshape the fabric of Russian society and influence international relations for decades to come. While the revolution promised a new era of equality and social justice, the reality often fell short, giving rise to authoritarianism, political repression, and economic hardships. The Soviet Union’s eventual emergence as a global superpower and its ideological rivalry with the capitalist West would define much of the 20th century, leading to the Cold War and a host of geopolitical tensions.

As we reflect on the legacy of the Russian Revolution, it becomes clear that its impact extends far beyond the immediate aftermath of 1917. The ideals of socialism and communism, although transformed and challenged over time, continue to resonate in political discourse around the world. The revolution serves as a potent reminder of the power of radical change and the complex interplay between ideology, governance, and human rights. Understanding this historical moment provides valuable insights into the forces that shaped the modern world and the enduring quest for societal transformation.