The Ming Dynasty, a pivotal chapter in Chinese history, stands as a beacon of cultural brilliance and administrative innovation. Spanning from 1368 to 1644, this era marked a period of profound transformation, bridging the gap between the medieval and early modern periods of China. Emerging from the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty, the Ming Dynasty was founded by Zhu Yuanzhang, who transformed a fragmented empire into a centralized and prosperous state.

Under the Ming rule, China experienced a renaissance in art, architecture, and literature. The dynasty is renowned for its exquisite porcelain, majestic architectural feats such as the Forbidden City, and vibrant literary works that continue to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike. The era also saw significant advancements in governance, with reforms aimed at reducing corruption and strengthening the bureaucracy.

However, the Ming Dynasty’s legacy is not solely defined by its achievements. The latter part of the dynasty was marked by internal strife, economic difficulties, and eventual decline, culminating in its fall to the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty in 1644. This comprehensive overview explores the Ming Dynasty’s origins, governance, cultural contributions, and eventual decline, offering a detailed look into a dynasty that profoundly shaped China’s historical trajectory and cultural heritage.

(commons.wikipedia)

Origins and Establishment

(Founding of the Ming Dynasty)

The Ming Dynasty emerged in the late 14th century, following the decline and eventual collapse of the Yuan Dynasty. The Yuan Dynasty, established by Kublai Khan and the Mongol Empire, faced widespread dissatisfaction due to its foreign Mongol rule, corruption, and administrative inefficiencies. The heavy taxation and mismanagement led to widespread suffering among the Han Chinese population.

Zhu Yuanzhang, a former peasant from the region of present-day Anhui, rose from humble beginnings to become a key figure in the struggle against the Yuan. Initially, he joined the Red Turban Rebellion, a popular uprising that sought to end Mongol rule and address the economic and social grievances of the Chinese people. Zhu’s leadership, military acumen, and ability to rally support from various factions played a crucial role in the rebellion’s success.

By 1368, Zhu Yuanzhang had successfully overthrown the last Yuan emperor, Shun, and declared himself the Hongwu Emperor, marking the beginning of the Ming Dynasty. His reign symbolized the restoration of Han Chinese control over China and the end of Mongol dominance. The new dynasty’s name, “Ming,” meaning “brilliant” or “luminous,” reflected the hope of a new era of prosperity and enlightened rule.

(Early Reforms and Consolidation)

Hongwu’s reign was marked by a determined effort to consolidate power and stabilize the country. His initial focus was on rebuilding the war-torn nation and addressing the issues that had plagued the Yuan Dynasty. Key reforms implemented during his early years included:

-

Restoration of the Civil Service Examination System: Hongwu revived the civil service examination system, which had been neglected under the Yuan. This system allowed for the recruitment of talented officials based on merit rather than aristocratic privilege or corruption. By reestablishing this system, Hongwu aimed to create a more effective and accountable bureaucracy.

-

Centralization of Power: The Hongwu Emperor worked to centralize administrative power by curbing the influence of local warlords and reducing the power of eunuchs within the court. He restructured the government into a centralized bureaucracy, with a clear hierarchy of officials and ministries overseeing various aspects of governance. This centralization was crucial for maintaining order and implementing the emperor’s policies throughout the empire.

-

Agrarian Development and Fiscal Reforms: Recognizing the importance of agriculture in sustaining the economy, Hongwu implemented policies to improve agricultural productivity. He promoted land reclamation, improved irrigation systems, and offered incentives to farmers. Additionally, he introduced fiscal reforms to streamline taxation and reduce the burden on peasants, aiming to create a more equitable and efficient tax system.

-

Anti-Corruption Measures: The Hongwu Emperor took a strong stance against corruption and abuse of power. He established strict regulations and oversight mechanisms to prevent bribery and misconduct among officials. He also conducted regular inspections and audits to ensure that officials adhered to the laws and policies of the dynasty.

-

Military Reorganization: Hongwu reorganized the military to enhance its effectiveness and loyalty. He implemented a system of military households, where soldiers were granted land and responsibilities in exchange for their service. This helped ensure that the military remained well-trained, disciplined, and committed to the dynasty.

Through these reforms and consolidation efforts, the Hongwu Emperor laid the groundwork for the Ming Dynasty’s stability and longevity. His emphasis on agrarian development, bureaucratic efficiency, and anti-corruption measures set the stage for a period of relative peace and prosperity that would define the Ming era.

Governance and Administration

(The Centralized Bureaucracy)

The Ming Dynasty is renowned for its highly centralized bureaucracy, a hallmark of its administrative system. This centralization was crucial for maintaining control over a vast and diverse empire. The administrative framework was meticulously organized to ensure the efficient implementation of imperial policies and the management of state affairs.

1. Administrative Divisions: The Ming administrative system was divided into several key ministries, each responsible for specific areas of governance. These included:

- The Ministry of Personnel: Managed the appointment, promotion, and removal of officials. It was responsible for overseeing the civil service examination system and ensuring that qualified individuals were placed in positions of authority.

- The Ministry of Revenue: Handled fiscal matters, including taxation, state finances, and economic policies. It played a crucial role in managing the empire’s resources and budget.

- The Ministry of Rites: Oversaw ceremonial matters, including state rituals, diplomatic protocols, and Confucian education. It was also responsible for managing relations with foreign envoys and maintaining the imperial court’s ceremonial traditions.

- The Ministry of War: Directed military affairs, including defense, military campaigns, and the maintenance of armed forces. It was responsible for coordinating military strategy and ensuring the empire’s security.

- The Ministry of Justice: Administered legal matters and the judicial system. It dealt with criminal cases, legal disputes, and the implementation of laws and regulations.

2. The Grand Secretariat: At the apex of the Ming bureaucracy was the Grand Secretariat, a key institution responsible for assisting the emperor in the administration of the empire. The Grand Secretariat comprised high-ranking officials who helped draft edicts, manage state documents, and coordinate the activities of the various ministries. They played a central role in ensuring that the emperor’s directives were executed efficiently.

3. Provincial Administration: To manage the vast territory of the Ming Empire, the central government established a hierarchical system of provincial administration. China was divided into provinces, each governed by a provincial governor who was responsible for local administration, law enforcement, and tax collection. The provincial governors were appointed by the central government and were expected to report directly to the emperor or the relevant ministries.

4. Local Governance: Beneath the provincial level, the Ming Dynasty also established county and district administrations. Local officials, such as magistrates and district administrators, were tasked with implementing imperial policies at the grassroots level. They were responsible for local law enforcement, public welfare, and tax collection. This tiered system of governance helped maintain order and facilitate communication between the central government and local communities.

(The Role of the Emperor)

The emperors of the Ming Dynasty held supreme authority and were considered divine rulers, embodying the Mandate of Heaven, a concept that justified their right to rule. Their role encompassed several key aspects:

1. Supreme Authority: As the central figure in the Ming political system, the emperor wielded absolute power over state affairs. They were the ultimate decision-maker on matters of governance, policy, and military strategy. The emperor’s authority was supported by a complex bureaucracy, but ultimate control rested in their hands.

2. Divine Rulership: The Ming emperors were viewed as divinely ordained rulers, a belief that reinforced their legitimacy and authority. This divine status was linked to the concept of the Mandate of Heaven, which held that the emperor’s right to rule was granted by divine will. The emperor was expected to uphold moral virtue and benevolence, ensuring the prosperity and well-being of the empire and its people.

3. Patronage of Arts and Culture: Ming emperors were notable patrons of the arts, and their reign saw a flourishing of cultural achievements. The emperors supported various artistic endeavors, including painting, calligraphy, literature, and porcelain production. Their patronage helped establish distinctive Ming artistic styles and contributed to the development of cultural traditions that have had a lasting impact on Chinese heritage.

4. Imperial Ceremonies and Rituals: The emperor played a central role in state ceremonies and rituals, which were crucial for maintaining the social and political order. The emperor performed rituals related to agriculture, ancestral worship, and state ceremonies to reinforce their divine status and legitimacy. These rituals also served to communicate the emperor’s benevolence and commitment to the welfare of the state.

5. Governance and Policy Implementation: In addition to their symbolic and ceremonial roles, Ming emperors were actively involved in the day-to-day governance of the empire. They issued edicts, oversaw the implementation of laws, and made strategic decisions on military and foreign affairs. The emperors were expected to be hands-on in their administration, frequently meeting with officials, reviewing reports, and making key policy decisions.

The Ming Dynasty’s governance structure and the role of the emperor were integral to the dynasty’s ability to manage its vast empire effectively. The centralized bureaucracy ensured that imperial policies were implemented consistently across the empire, while the emperor’s divine authority and patronage of the arts reinforced their legitimacy and the cultural vibrancy of the Ming era.

Economic and Social Developments

(Economic Growth)

1. Agricultural Productivity: The Ming Dynasty saw remarkable advancements in agriculture, which played a central role in its economic growth. Significant improvements in irrigation technology, such as the construction of new canals and the repair of existing ones, greatly enhanced agricultural productivity. The expansion and maintenance of the Grand Canal, a vital waterway linking the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, facilitated the efficient transportation of grain and other goods. Additionally, the introduction of new crops and farming techniques, such as the adoption of drought-resistant strains and crop rotation systems, contributed to increased yields and agricultural stability.

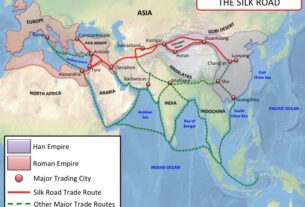

2. Trade and Commerce: Trade, both domestic and international, flourished during the Ming Dynasty. The period saw a significant increase in commercial activity, driven by advancements in transportation and communication. The establishment of a robust network of trade routes, including the maritime Silk Road, facilitated the exchange of goods between China and various regions in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. The Ming Dynasty’s trade policies encouraged both internal and external trade, with major port cities like Guangzhou (Canton) and Ningbo becoming bustling centers of commerce.

3. Technological Advancements: The Ming era was marked by technological innovation, particularly in the fields of agriculture, manufacturing, and navigation. Advances in agricultural tools and techniques improved efficiency and productivity. In manufacturing, the production of Ming porcelain, renowned for its quality and artistry, became a major economic driver. The development of advanced shipbuilding techniques also enhanced China’s maritime capabilities, supporting both trade and exploration.

4. Rise of the Merchant Class: The Ming Dynasty witnessed the emergence of a prosperous merchant class, which played a crucial role in the economy. The expansion of trade and commerce created opportunities for merchants to accumulate wealth and influence. This new class contributed to the growth of urban centers and the development of a vibrant market economy. Despite facing occasional restrictions and social stigma, merchants gained significant economic power and contributed to the dynamic nature of Ming society.

5. Urbanization and Infrastructure: Urbanization accelerated during the Ming Dynasty, with the growth of cities and towns reflecting the empire’s economic vitality. The development of infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and markets, supported urban expansion and facilitated economic activities. Major cities such as Beijing, Nanjing, and Hangzhou became bustling commercial and cultural hubs, attracting people from various regions and contributing to the overall prosperity of the empire.

(Social Structure and Conflicts)

1. Hierarchical Social Structure: Ming society was organized into a hierarchical class structure, reflecting traditional Chinese values and Confucian principles. At the top of the hierarchy was the emperor, followed by the nobility, which included aristocratic families and high-ranking officials. Below them were scholars, who were highly respected for their education and intellectual achievements. Farmers, artisans, and merchants occupied lower tiers of the social hierarchy, with farmers being particularly valued for their contribution to agricultural production.

2. Social Mobility and Scholar-Officials: Despite the rigid social structure, the Ming Dynasty saw significant social mobility, particularly through the civil service examination system. This system allowed individuals from non-aristocratic backgrounds to attain high-ranking positions based on merit. The rise of scholar-officials, who were selected through rigorous examinations and served as government administrators, contributed to increased social mobility and the influence of educated elites. Scholar-officials played a key role in shaping policy, administering justice, and contributing to the cultural and intellectual life of the empire.

3. Conflicts and Tensions: Social and economic tensions were a recurring feature of Ming society. Conflicts often arose between different social classes and regions, driven by issues such as land distribution, taxation, and corruption. Peasant uprisings and local rebellions occasionally challenged the authority of the central government, reflecting underlying discontent and grievances among the lower classes. Additionally, the growing influence of the merchant class sometimes clashed with traditional Confucian values, which emphasized the importance of agricultural and scholarly pursuits over commercial activities.

4. Cultural and Social Changes: The Ming Dynasty was a period of significant cultural and social transformation. The flourishing of arts, literature, and education contributed to a vibrant cultural atmosphere. Social changes, including increased interactions between different regions and cultures, influenced the development of new ideas and practices. The Ming period also saw the spread of Neo-Confucianism and the adaptation of traditional values to changing social realities.

5. Family and Gender Roles: Traditional family structures and gender roles remained influential during the Ming Dynasty. Confucian values emphasized the importance of filial piety, hierarchical family relationships, and gender-specific roles. However, the period also saw gradual changes in family dynamics and gender roles, influenced by economic developments and social transformations. Women’s roles, while generally constrained by Confucian norms, saw some variation depending on region and social status.

Overall, the Ming Dynasty’s economic growth and social developments were interlinked, with advancements in agriculture, trade, and technology contributing to a period of prosperity and urbanization. At the same time, the hierarchical social structure and emerging tensions reflected the complexities of managing a large and diverse empire.

Culture and Achievements

(Art and Architecture)

1. Ming Porcelain: One of the most enduring legacies of the Ming Dynasty is its porcelain, which reached new heights of quality and artistic expression during this period. Ming porcelain, particularly the blue-and-white ware, became highly prized both domestically and internationally. The distinctive blue-and-white designs were achieved using cobalt pigment under a clear glaze, creating intricate patterns and vibrant colors. These porcelains were not only functional but also served as significant artistic and decorative items. The Ming porcelain industry thrived with centers such as Jingdezhen, which became renowned for producing exquisite ceramics that were exported to Europe, the Middle East, and other parts of Asia.

2. Painting: The Ming Dynasty witnessed a flourishing of painting, with a diversity of styles and subjects. Ming painting is characterized by its emphasis on realistic representation, intricate detail, and rich color. Major styles included:

- Court Paintings: These were produced for the imperial court and often depicted historical events, portraits of emperors, and scenes from court life. Artists like the famous court painter Shen Zhou made significant contributions in this genre.

- Landscape Paintings: This genre continued to evolve from earlier traditions, with artists such as Wang Wei and Dong Qichang exploring new techniques and perspectives. Ming landscape paintings are noted for their detailed depiction of natural scenery and the incorporation of poetic elements.

- Figure Paintings: The Ming period saw the rise of figure painting, which focused on human subjects, including historical figures, gods, and mythical creatures. Artists such as Xu Wei and Chen Hongshou excelled in this genre, bringing innovative approaches to traditional themes.

3. Calligraphy: Calligraphy was highly esteemed during the Ming Dynasty, and it continued to be a crucial aspect of Chinese art and culture. Ming calligraphy is known for its varied styles, including regular script (kaishu), cursive script (caoshu), and semi-cursive script (xingshu). The period saw contributions from master calligraphers like Wang Shizhen and Zhu Yunming, who refined traditional techniques and developed distinctive personal styles. Calligraphy was not only a form of artistic expression but also a demonstration of one’s intellectual and moral character.

4. Architecture: The Ming Dynasty is celebrated for its impressive architectural achievements, including the construction of monumental structures and urban planning. Key examples include:

- The Forbidden City: Located in Beijing, the Forbidden City was the imperial palace complex and served as the political and ceremonial heart of the Ming Dynasty. Covering approximately 180 acres, the complex is renowned for its grandeur, intricate design, and the use of traditional Chinese architectural principles. The Forbidden City features nearly 1,000 buildings with ornate decoration and meticulous layout, reflecting the emperor’s supreme authority and the cultural values of the time.

- The Great Wall of China: During the Ming Dynasty, the Great Wall was extensively rebuilt and fortified. The Ming-era Wall, characterized by its watchtowers, defensive walls, and beacon towers, was constructed using brick and stone, making it more durable and effective in defense compared to earlier versions. The Ming Wall stretches across northern China and stands as a testament to the era’s military engineering and architectural ingenuity.

- Temple Architecture: Ming-era temples, including the Temple of Heaven and the Temple of Confucius, exemplify the dynasty’s architectural achievements. These temples were designed with meticulous attention to geomantic principles and served as important centers for religious and ceremonial activities.

(Literature and Scholarship)

1. Historical and Philosophical Works: The Ming Dynasty was a golden age for Chinese literature and scholarship, with significant contributions to historical writing, philosophy, and classical studies. Scholars produced comprehensive historical texts, such as the “Ming Shi” (History of the Ming Dynasty), which provided detailed accounts of the dynasty’s events and rulers. Philosophers and scholars engaged in the study and interpretation of Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist texts, contributing to the intellectual vibrancy of the era.

2. Literary Figures:

- Tang Xianzu: Often referred to as the “Shakespeare of China,” Tang Xianzu was a prominent playwright of the Ming Dynasty. His most famous work, “The Peony Pavilion,” is a classic of Chinese drama and literature. The play is celebrated for its poetic language, elaborate stagecraft, and exploration of themes such as love and dreams. Tang’s plays were influential in the development of Chinese theater and continue to be performed and studied today.

- Xu Wei: A versatile artist and writer, Xu Wei made significant contributions to both painting and literature. His works include innovative plays and essays that reflect his unique perspectives and artistic style. Xu Wei’s writing often explored themes of individualism and social critique, distinguishing him from his contemporaries.

3. Literary and Artistic Achievements: The Ming era produced a wealth of literary and artistic achievements, including novels, essays, and poetry. The period saw the rise of vernacular literature, which made literary works more accessible to a broader audience. Notable novels from this period include “Journey to the West” and “Water Margin,” which are considered masterpieces of Chinese fiction and have had a lasting impact on Chinese culture and literature.

4. Scholarly Institutions: The Ming Dynasty also saw the development of scholarly institutions and academies, which played a key role in the promotion of education and intellectual exchange. These institutions provided a platform for scholars to engage in academic discussions, conduct research, and produce influential works. The emphasis on education and scholarship contributed to the era’s cultural and intellectual flourishing.

Overall, the Ming Dynasty’s contributions to art, architecture, literature, and scholarship were marked by creativity, innovation, and a deep respect for tradition. The period’s achievements continue to be celebrated and studied, reflecting the enduring legacy of Ming culture and its impact on Chinese history.

Exploration and Foreign Relations

(Maritime Expeditions)

1. Admiral Zheng He and the Treasure Voyages: One of the most remarkable achievements of the Ming Dynasty was its ambitious maritime exploration under the command of Admiral Zheng He. Zheng He, originally named Cheng Ho, was a Muslim eunuch and a trusted advisor to the Yongle Emperor. He led a series of large-scale naval expeditions known as the Treasure Voyages, which took place between 1405 and 1433.

2. Scope and Objectives: Zheng He’s expeditions were aimed at establishing and consolidating China’s influence across Asia and Africa. His fleet comprised hundreds of massive treasure ships, some reportedly over 400 feet long, along with smaller auxiliary vessels. The voyages covered a vast geographical area, including:

- Southeast Asia: Zheng He’s expeditions reached ports in present-day Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, fostering trade and diplomatic relations with regional kingdoms.

- South Asia: The fleet visited regions of India, including the city of Calicut, where Zheng He established trade links and diplomatic ties with local rulers.

- Arabian Peninsula: Zheng He’s expeditions extended to the Arabian Peninsula, visiting cities such as Aden and engaging in diplomatic and commercial exchanges.

- East Coast of Africa: Zheng He’s voyages reached as far as the Swahili coast of East Africa, including present-day Kenya and Tanzania, where he established diplomatic relations and conducted trade.

3. Diplomatic and Trade Relations: The voyages of Zheng He were instrumental in expanding China’s influence and establishing diplomatic and trade relationships with various foreign powers. The Ming court received tribute from numerous states and regions, and the expeditions helped to secure China’s position as a dominant maritime power. The missions facilitated the exchange of goods, culture, and knowledge, and helped to enhance China’s prestige on the international stage.

4. Decline of Maritime Expeditions: Despite their initial success, Zheng He’s expeditions were not continued with the same intensity after his death and the death of the Yongle Emperor. The subsequent Ming rulers, particularly under Emperor Xuande and his successors, adopted a more conservative approach. The vast resources required for such large-scale maritime ventures became a point of contention, and the government shifted focus toward more pressing internal concerns.

(Foreign Relations and Isolationism)

1. Shift to Isolationism: Following the era of Zheng He, the Ming Dynasty gradually adopted a more isolationist foreign policy. This shift was influenced by several factors:

- Internal Stability and Defense: The later Ming emperors prioritized internal stability and the defense of the empire’s borders. The growing threat of invasions from the north, particularly by the Mongols and later the Manchu, required substantial resources and attention.

- Economic Concerns: The cost of maintaining a large navy and engaging in extensive foreign trade became a burden. The government redirected its focus to managing domestic affairs and fiscal stability.

2. Restrictive Policies: The Ming Dynasty implemented several policies to curtail foreign interaction and trade:

- Maritime Trade Restrictions: The Ming government imposed restrictions on maritime trade, limiting the activities of private merchants and reducing the scale of international trade. The maritime trade policies were formalized in a series of edicts that prohibited private seafaring and restricted foreign commerce to designated ports.

- Tributary System: The Ming Dynasty maintained a tributary system in which neighboring states were required to pay tribute to China in exchange for trade privileges and diplomatic recognition. While this system allowed for some controlled interaction with foreign powers, it was limited in scope compared to the earlier period of active maritime engagement.

3. Diplomatic Relations: Despite the shift towards isolationism, the Ming Dynasty continued to engage in diplomatic relations with neighboring states and regional powers. The empire maintained a network of diplomatic envoys and tribute missions, ensuring that it retained a degree of influence in regional affairs. However, the focus was largely on securing the empire’s borders and managing internal issues rather than expanding foreign relations.

4. Long-Term Implications: The Ming Dynasty’s transition to isolationism had significant long-term implications for China’s foreign relations and trade policies. The reduction in maritime activity and engagement with foreign powers contributed to a gradual decline in China’s global influence. The emphasis on internal affairs and defense shaped the course of China’s subsequent history, including its interactions with European powers and its eventual response to external pressures in later centuries.

Overall, the Ming Dynasty’s era of maritime exploration and subsequent shift towards isolationism reflects a complex interplay of ambitions, resources, and priorities. The legacy of Zheng He’s voyages and the broader impact of the Ming foreign policy continue to be subjects of historical interest and analysis.

Decline and Fall

(Internal Struggles and Corruption)

1. Eunuchs and Court Factions: As the Ming Dynasty progressed into its later years, internal power struggles and corruption increasingly undermined the stability of the regime. A significant factor was the growing influence of eunuchs at the imperial court. Eunuchs, who were castrated men employed in various administrative and household roles, began to wield substantial political power. Their influence led to intense rivalries and factionalism within the court, as different groups vied for control and sought to gain favor with the emperor.

Eunuchs often engaged in corrupt practices, including bribery and embezzlement, which further eroded the effectiveness of the central government. Their manipulation of court politics and their control over important posts created a volatile environment that weakened the authority of the emperors and contributed to administrative inefficiency.

2. Economic Difficulties: The Ming Dynasty faced severe economic difficulties in its later years, exacerbated by both internal mismanagement and external pressures. Frequent natural disasters, such as floods, droughts, and famines, placed immense strain on the agricultural sector and led to widespread suffering. These disasters not only disrupted food production but also placed additional burdens on the state’s finances.

Economic hardships were compounded by heavy taxation and inflation, which led to widespread discontent among the peasantry. The economic strain contributed to social unrest and weakened the government’s ability to respond effectively to internal and external challenges.

3. Military Defeats and Border Instability: The Ming Dynasty experienced a series of military defeats and setbacks that further eroded its power. The northern borders, particularly the region along the Great Wall, were vulnerable to incursions by Mongol and Manchu tribes. The Ming military, plagued by corruption and inefficiency, struggled to defend against these incursions.

In addition to external threats, internal rebellions and uprisings became increasingly frequent. The most notable of these was the rise of peasant rebel groups, such as the Li Zicheng-led Shun Dynasty forces, which exploited the widespread discontent to challenge the Ming regime.

4. Corruption and Administrative Breakdown: Corruption and mismanagement within the Ming bureaucracy further exacerbated the dynasty’s decline. Officials often engaged in corrupt practices, such as accepting bribes and embezzling state funds. This corruption undermined the effectiveness of government institutions and led to widespread inefficiency in administration and law enforcement.

The failure to address these systemic issues contributed to the erosion of public trust and the weakening of central authority. The inability to effectively govern and manage the empire’s vast territory left the Ming Dynasty vulnerable to internal and external threats.

(The Fall of the Ming Dynasty)

1. The Rebel Uprising: The final years of the Ming Dynasty were marked by intense internal strife and rebellion. The most significant uprising was led by Li Zicheng, a former peasant who gathered a large following of disaffected peasants and soldiers. Li’s forces captured Beijing in 1644, leading to the collapse of the Ming government.

2. The Suicide of Emperor Chongzhen: As the rebel forces advanced on the capital, the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen, faced mounting pressure and despair. On April 25, 1644, as Beijing was overtaken by the rebels, Emperor Chongzhen committed suicide by hanging himself in the Jingshan Park, a tragic end that marked the official fall of the Ming Dynasty.

3. The Manchu Invasion and the Establishment of the Qing Dynasty: Following the fall of Beijing, the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty, which had initially supported Ming loyalists, seized the opportunity to consolidate power. The Manchu forces, led by the Hong Taiji and later Emperor Shunzhi, advanced southward and defeated the remaining Ming loyalist forces. By 1644, the Qing Dynasty had established control over most of China, bringing an end to the Ming era.

The Qing Dynasty, founded by the Manchu people from northeastern China, became the new ruling power. It consolidated its control over China, ushering in a new era that would last until the early 20th century. The transition from the Ming to the Qing Dynasty marked a significant shift in Chinese history, with profound implications for the country’s political, social, and cultural landscape.

4. Historical Legacy: The fall of the Ming Dynasty and the rise of the Qing Dynasty represented a major turning point in Chinese history. The Ming era is remembered for its cultural and artistic achievements, as well as its complex political and social dynamics. The legacy of the Ming Dynasty continues to be studied and appreciated for its contributions to China’s rich historical and cultural heritage.

Legacy

(Cultural and Artistic Impact)

Porcelain and Ceramics: The Ming Dynasty is celebrated for its remarkable advancements in porcelain and ceramics, particularly for its iconic blue-and-white wares. Ming porcelain, renowned for its fine quality and intricate designs, became a symbol of Chinese craftsmanship and artistry. The period’s porcelain production, characterized by its use of cobalt blue underglaze, set a high standard that influenced ceramic art globally. The techniques and styles developed during the Ming era continued to inspire and shape porcelain production in subsequent dynasties, including the Qing Dynasty. This influence extended beyond China, impacting ceramic traditions in other parts of Asia and Europe, where Ming porcelain became highly prized and sought after by collectors and connoisseurs.

Art and Architecture: The Ming Dynasty’s contributions to art and architecture left a lasting imprint on Chinese cultural heritage. Architecturally, the construction of the Forbidden City in Beijing stands as a monumental achievement of Ming-era engineering and design. This vast palace complex, with its grandiose halls, intricate wooden carvings, and expansive courtyards, exemplifies the dynasty’s architectural prowess and its emphasis on harmony and grandeur. Additionally, the extensive renovation of the Great Wall of China during the Ming period not only enhanced its defensive capabilities but also demonstrated the era’s commitment to safeguarding the empire.

In art, the Ming Dynasty witnessed the flourishing of various forms, including painting and calligraphy. The period is known for its distinct artistic styles, such as the realistic and detailed landscape paintings of Shen Zhou and the elegant brushwork of calligraphers like Wang Shizu. These artistic achievements continue to influence contemporary Chinese art and design, and the principles and techniques developed during the Ming era remain celebrated in modern artistic practices.

Literature and Drama: The Ming Dynasty is regarded as a golden age of Chinese literature and drama. This period saw the emergence of classic literary works that have had a lasting impact on Chinese cultural and literary traditions. Tang Xianzu’s “The Peony Pavilion,” a masterpiece of Chinese drama, is celebrated for its lyrical beauty and exploration of themes such as love, dreams, and social norms. The Ming era also saw the development of the novel as a literary form, with seminal works like “Journey to the West” and “The Water Margin” capturing the imagination of readers and establishing enduring narratives in Chinese literature. These contributions continue to be studied, performed, and appreciated for their artistic and cultural significance.

(Governance and Administration)

Civil Service Examination System: One of the Ming Dynasty’s most enduring legacies is its emphasis on the civil service examination system. This system was designed to select government officials based on merit rather than hereditary privilege, promoting a more equitable and efficient bureaucratic structure. The civil service examinations, which tested candidates on Confucian classics and administrative skills, became a cornerstone of Chinese governance and set a standard for future dynasties. The principles established during the Ming era continued to influence the selection and training of officials in subsequent periods, contributing to the development of a meritocratic bureaucracy that remained central to Chinese governance.

Administrative Reforms: The Ming Dynasty’s administrative reforms were pivotal in shaping the governance of the empire. Efforts to combat corruption and centralize authority were integral to the dynasty’s administration. The establishment of a more structured bureaucratic system, coupled with reforms aimed at improving fiscal management and reducing corruption, set precedents for future governance. These administrative practices, including the strengthening of local governance and the creation of specialized ministries, influenced the political institutions of subsequent dynasties and contributed to the evolution of Chinese administrative practices.

(Historical and Intellectual Legacy)

Historiography: The Ming Dynasty made significant contributions to historiography, with comprehensive historical records such as the “Ming Shi” (History of the Ming Dynasty) providing detailed accounts of the era’s events and developments. These historical works set a high standard for Chinese historiography, emphasizing rigorous research and detailed documentation. The approach to historical writing developed during the Ming period influenced the methods and practices of historians in later periods, contributing to the development of Chinese historiographical traditions.

Philosophy and Thought: The Ming era was a period of vibrant intellectual activity, with significant contributions to Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist thought. The period saw a renewed emphasis on Confucian principles, coupled with explorations of Daoist and Buddhist philosophies. This intellectual engagement helped shape the philosophical and cultural landscape of China, influencing subsequent philosophical developments and contributing to the rich tapestry of Chinese thought. The Ming Dynasty’s intellectual legacy continues to be studied and appreciated for its impact on Chinese philosophy and cultural practices.

(Influence on Modern China)

Cultural Heritage: The Ming Dynasty’s cultural achievements are celebrated as integral components of China’s historical and cultural heritage. The dynasty’s contributions to art, literature, and architecture are preserved and valued as symbols of national identity and pride. Modern China continues to honor and celebrate these contributions through various cultural heritage initiatives, including the preservation of historical sites, museums, and academic studies that highlight the dynasty’s lasting impact.

Historical Reflections: The Ming era is often viewed as a bridge between the medieval and early modern periods in Chinese history. Its achievements and challenges provide important insights into the evolution of Chinese society, governance, and culture. The lessons learned from the Ming Dynasty’s successes and struggles offer valuable perspectives on the complexities of Chinese history and the ongoing development of the nation.

(International Impact)

Global Trade and Diplomacy: The Ming Dynasty’s maritime expeditions, led by Admiral Zheng He, had a profound impact on global trade and diplomacy. Zheng He’s voyages established China’s presence on the international stage, fostering diplomatic and trade relations with various regions, including Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, and the East Coast of Africa. The legacy of these expeditions highlights China’s historical role in global exploration and intercultural exchange, contributing to a broader understanding of China’s influence in world history.

(Preservation and Legacy Projects)

Cultural Preservation: Efforts to preserve Ming-era sites, artifacts, and historical records reflect a commitment to maintaining the dynasty’s legacy for future generations. Restoration projects and cultural heritage initiatives aim to safeguard the physical and intangible contributions of the Ming era, ensuring that its achievements and history continue to be recognized and appreciated. These preservation efforts contribute to a deeper understanding of the Ming Dynasty’s impact and help keep its legacy alive in contemporary society.

Overall, the Ming Dynasty’s legacy is characterized by its profound and lasting contributions to Chinese culture, governance, and history. Its achievements in art, literature, administration, and international relations continue to be celebrated and studied, reflecting the enduring impact of this significant period in Chinese history.

Conclusion,

The Ming Dynasty’s legacy is a tapestry woven with threads of innovation, grandeur, and complexity. From its origins in the upheaval of the Yuan Dynasty to its zenith as a cultural and administrative powerhouse, the Ming era profoundly shaped China’s historical landscape. The dynasty’s contributions to art, with its renowned porcelain and architectural masterpieces like the Forbidden City, have left an indelible mark on both Chinese culture and global heritage.

The Ming Dynasty’s commitment to reforming governance and revitalizing the civil service examination system set enduring precedents for administrative practices. Its maritime explorations under Admiral Zheng He expanded China’s influence far beyond its borders, fostering international connections that resonate in historical studies and cultural exchanges today.

Yet, the dynasty’s decline, characterized by internal discord, corruption, and economic strain, serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of even the most powerful empires. The fall of the Ming Dynasty to the Qing forces ushered in a new era, but the achievements and lessons of the Ming period continue to be a source of reflection and inspiration.

As we look back on the Ming Dynasty, we see a period that not only bridged two significant epochs in Chinese history but also left a lasting legacy that continues to be celebrated and studied. Its contributions to art, literature, and governance provide valuable insights into the dynamic interplay between culture and power, making the Ming Dynasty an enduring symbol of China’s rich historical heritage.