Buddhism, a profound and transformative spiritual tradition, originated in the 6th century BCE in what is now modern-day Nepal and northern India. Founded by Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha, this philosophy of life aimed at overcoming suffering and achieving enlightenment quickly extended beyond its geographical origins. What began as a local movement soon embarked on a remarkable journey across Asia, influenced by a series of historical, cultural, and political factors.

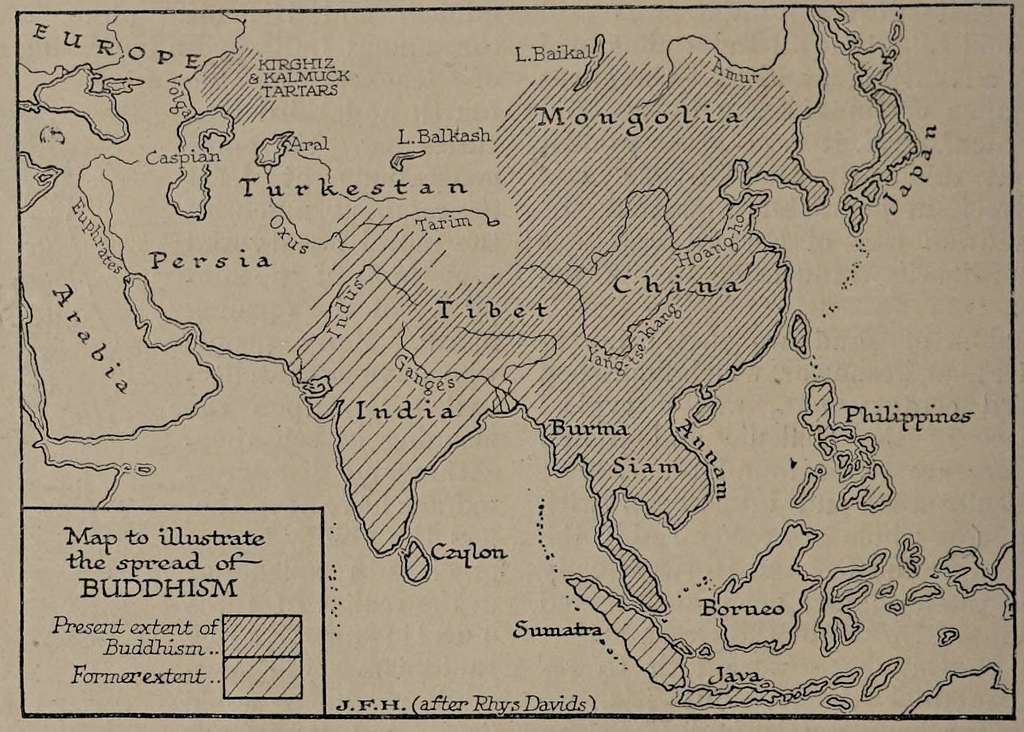

The spread of Buddhism across Asia is a compelling story of adaptation and integration. From its early foothold in India to its far-reaching influence in Central Asia, China, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia, Buddhism adapted to diverse cultural landscapes, shaping and being shaped by the regions it touched. This expansive journey was marked by the establishment of monastic communities, the patronage of powerful emperors, and the cross-cultural exchanges facilitated by trade routes and missionary efforts. As Buddhism spread, it left an indelible mark on art, architecture, philosophy, and social practices across the continent, evolving into a major world religion with a rich and varied heritage.

This article delves into the intricate and multi-faceted spread of Buddhism across Asia, exploring how it traversed diverse regions and cultures, and examining the profound impacts it had on each of these societies. From its origins in India to its establishment in distant lands, the story of Buddhism’s expansion is a testament to its adaptability and enduring relevance in the spiritual and cultural fabric of Asia.

(Commons.wikipedia)

Origins of Buddhism

Buddhism traces its roots to the 6th century BCE in the region that is now modern-day Nepal and northern India. The founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama, was born into a royal family in the Shakya clan, in the small kingdom of Kapilavastu, located near the border of present-day Nepal. His exact birth date is debated, but it is traditionally placed around 563 BCE. Siddhartha was raised in a life of luxury and privilege, shielded from the harsh realities of life by his father, King Suddhodana, who hoped his son would one day become a great ruler. Siddhartha’s early life was marked by comfort and protection, designed to keep him away from any knowledge of suffering or hardship.

Despite the comforts of palace life, Siddhartha’s curiosity about the world beyond the palace walls grew stronger. At the age of 29, he ventured outside the palace and encountered what are known as the Four Sights: an old man, a sick man, a dead body, and an ascetic monk. These encounters were deeply disturbing for Siddhartha, as they revealed to him the inevitable suffering that all beings experience, such as aging, illness, and death, and sparked his existential quest for meaning. The sight of the ascetic monk, who had renounced worldly pleasures in search of spiritual truth, particularly inspired Siddhartha to seek his own path to enlightenment.

(The Four Sights)

The Four Sights profoundly impacted Siddhartha Gautama, leading him to question the purpose of life and the nature of human suffering. The old man represented the inevitability of aging, the sick man illustrated the reality of illness, the dead body demonstrated the finality of death, and the ascetic monk embodied the quest for liberation from suffering. These revelations led Siddhartha to realize that a life of luxury and comfort could not shield him from the universal truths of suffering and impermanence. This new understanding catalyzed his decision to renounce his royal life in search of spiritual enlightenment.

Determined to find answers, Siddhartha abandoned his life of privilege, leaving behind his wife, Yasodhara, and their newborn son, Rahula. He embraced the life of a wandering ascetic, seeking wisdom from various spiritual teachers of his time. Despite mastering their teachings, Siddhartha found their paths insufficient for answering his deep existential questions. This realization led him to pursue a path of extreme asceticism, characterized by severe self-deprivation, which he hoped would bring him closer to enlightenment and liberation from suffering.

(Renunciation and Ascetic Practice)

Siddhartha Gautama’s journey into asceticism involved extreme self-denial, including severe austerities such as fasting and prolonged meditation. For six years, he subjected himself to harsh practices, believing that overcoming physical desires and comforts would lead to spiritual awakening. However, this rigorous approach resulted in physical weakness and did not bring him the enlightenment he sought. Siddhartha eventually recognized that such extreme practices were not the true path to wisdom, leading him to reconsider his approach to spiritual attainment.

Realizing that neither indulgence nor extreme asceticism was effective, Siddhartha adopted a more balanced approach known as the Middle Way. This philosophy emphasized moderation and avoided the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification. By embracing a balanced lifestyle, Siddhartha aimed to cultivate a state of mental clarity and insight that would facilitate his quest for enlightenment. His new approach would later become a core principle of Buddhist practice, guiding future practitioners toward a path of moderation and mindfulness.

(Enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree)

At the age of 35, Siddhartha Gautama seated himself under a pipal tree, later known as the Bodhi tree, in Bodh Gaya, India, and resolved to remain in meditation until he achieved enlightenment. This pivotal moment marked the culmination of his quest for understanding the nature of existence and suffering. During his meditation, Siddhartha faced numerous temptations and distractions from Mara, the demon of illusion, who sought to prevent him from attaining enlightenment. Despite these challenges, Siddhartha remained steadfast, ultimately achieving a profound state of Nirvana.

The attainment of Nirvana signified Siddhartha’s realization of the true nature of existence and his liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (Samsara). At this moment, Siddhartha became the Buddha, or “the Awakened One,” having gained complete insight into the nature of suffering and the path to liberation. This profound awakening not only transformed Siddhartha’s own life but also laid the foundation for the teachings that would form the basis of Buddhism, guiding countless individuals on their own paths to enlightenment.

(Teaching and the Formation of the Sangha)

Following his enlightenment, the Buddha spent the next 45 years traveling across northern India, sharing his insights and teachings with a diverse range of followers. His first sermon, delivered in the Deer Park at Sarnath, introduced the core principles of Buddhism, including the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. These teachings offered a comprehensive framework for understanding and overcoming suffering, which became central to Buddhist doctrine. The Buddha’s teachings attracted a broad audience, including monks, nuns, and laypeople, reflecting the universal appeal of his message.

The formation of the Sangha, or monastic community, was crucial in preserving and disseminating the Buddha’s teachings. The Sangha provided a supportive network for practitioners and played a key role in maintaining the integrity of Buddhist teachings and practices. Unlike many other spiritual traditions of the time, Buddhism was inclusive and open to all individuals regardless of caste, gender, or social status. This inclusive nature contributed to Buddhism’s widespread appeal and its growth into a major religious tradition across Asia.

(Emphasis on Personal Experience)

The Buddha emphasized the importance of personal experience and self-effort in the pursuit of enlightenment, encouraging his followers to test his teachings through their own experience. This approach underscored the practical and experiential nature of Buddhist practice, which focused on individual insight rather than blind adherence to doctrine. The Buddha’s teachings encouraged followers to engage in personal reflection and meditation, fostering a deep and direct understanding of the nature of reality and the path to liberation.

This emphasis on personal experience and self-discovery distinguished Buddhism from other spiritual traditions of the time. By prioritizing individual insight and personal practice, the Buddha empowered his followers to explore and understand the teachings in a way that was meaningful and relevant to their own lives. This pragmatic approach remains a core aspect of Buddhism, guiding practitioners to cultivate their own understanding and experiences on the path to enlightenment.

(Passing Away and Legacy)

The Buddha passed away at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, India. His death is referred to as “Parinirvana,” representing the final cessation of suffering and the ultimate liberation from the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The Buddha’s passing marked the end of his physical presence but the beginning of a new phase for his teachings, which would be preserved and transmitted by his disciples. The oral transmission of his teachings eventually led to the compilation of the Tripitaka, or “Three Baskets,” which became the foundational scriptures of Buddhism.

The legacy of the Buddha’s teachings has had a profound and lasting impact on the world. Buddhism spread across India and eventually to other parts of Asia, evolving into various schools and traditions while maintaining the core principles of the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. The teachings of the Buddha continue to inspire millions of practitioners around the globe, guiding them on their journey toward liberation from suffering and offering timeless insights into the nature of existence.

Early Spread in India

After the Buddha’s death, traditionally dated to around 483 BCE, his followers, known as the Sangha, undertook the crucial task of preserving and disseminating his teachings across the Indian subcontinent. These early disciples played a pivotal role in ensuring that the Buddha’s message of the Middle Way, the Four Noble Truths, and the Eightfold Path reached diverse audiences. The Sangha’s dedication to teaching and preserving the Buddha’s doctrines laid the groundwork for the spread of Buddhism beyond its initial geographic and cultural boundaries.

The early Buddhist community established monasteries, or viharas, which functioned as centers for both religious practice and community life. These monasteries became key hubs for education, philosophical discourse, and social service, playing a central role in the spread of Buddhism. Monks traveled extensively, sharing the Buddha’s teachings with people from various backgrounds, and monasteries served as places where monks and laypeople could engage in spiritual practice and study. The monastic system was instrumental in Buddhism’s early expansion, providing a structured and supportive environment for the growth of the faith.

(Emperor Ashoka’s Conversion)

One of the most significant figures in the early spread of Buddhism was Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Dynasty, who ruled from 268 to 232 BCE. Ashoka’s reign marked a transformative period for Buddhism, elevating it from a localized movement to a major spiritual and cultural force across India and beyond. Ashoka’s initial rule was marked by military conquests and expansion, but the aftermath of the Kalinga War, which resulted in significant loss of life, led to a profound change in his outlook.

Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism is a notable episode in Indian history. Overcome by remorse for the devastation caused by his conquests, Ashoka embraced Buddhism’s teachings on non-violence, compassion, and righteousness. His newfound commitment to Buddhism profoundly influenced his reign, leading him to promote the faith and integrate its principles into his governance. This shift from a warrior king to a devout Buddhist monarch significantly impacted the growth and development of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent.

(Ashoka’s Contributions to Buddhism)

Following his conversion, Ashoka became a fervent supporter of Buddhism and undertook several initiatives to spread the faith both within and beyond his empire. He commissioned the construction of stupas, monumental dome-shaped structures that housed relics of the Buddha and became important centers of pilgrimage and devotion. The Great Stupa at Sanchi is one of the most renowned examples, continuing to be a major site of religious significance.

In addition to constructing stupas, Ashoka established numerous monasteries and supported educational institutions that fostered Buddhist learning. He convened the Third Buddhist Council around 250 BCE in Pataliputra (modern-day Patna), aiming to purify the Sangha and standardize Buddhist doctrine. This council played a crucial role in maintaining the integrity of Buddhist teachings and practices, contributing to the coherence and spread of Buddhism during Ashoka’s reign.

(Ashoka’s Edicts and Missionary Work)

Ashoka’s edicts, inscribed on pillars, rocks, and cave walls throughout his empire, are among his most enduring legacies. These inscriptions, written in languages such as Prakrit, Greek, and Aramaic, communicated Ashoka’s support for Buddhism and outlined his vision for a just and moral society. The edicts emphasized key Buddhist principles like non-violence (ahimsa), tolerance, and ethical conduct, providing valuable insights into the spread of Buddhism during his reign.

Ashoka also sent emissaries and missionaries to propagate Buddhism beyond his empire. His son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta were instrumental in introducing Buddhism to Sri Lanka, where it took deep root and eventually spread to Southeast Asia. Ashoka’s efforts to send missionaries to distant regions such as Greece, Egypt, and Central Asia helped lay the groundwork for Buddhism’s expansion into new territories, establishing a legacy that would shape the future of the religion.

(The Impact of Ashoka’s Patronage)

Under Ashoka’s patronage, Buddhism flourished and began to evolve doctrinally and culturally. The emperor’s support facilitated the proliferation of Buddhist texts, the development of Buddhist art, and the construction of monumental architecture. This period saw the emergence of early Buddhist art, characterized by stone carvings and reliefs depicting the Buddha’s life and teachings. Ashoka’s contributions provided a solid foundation for the continued growth and evolution of Buddhism across Asia.

Ashoka’s influence extended far beyond his reign, shaping the trajectory of Buddhism’s spread into Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and eventually East Asia. His patronage and missionary efforts were pivotal in transforming Buddhism from a regional movement into a major global religion. The enduring presence of Buddhism across Asia and its continued influence on spiritual, cultural, and social landscapes reflect the profound impact of Ashoka’s support and promotion of the faith.

(Summary)

The early spread of Buddhism in India was significantly shaped by the efforts of the Buddha’s followers and the transformative influence of Emperor Ashoka. The establishment of monastic communities, the construction of stupas, and the promotion of Buddhism by Ashoka were crucial in expanding the reach of the faith. Ashoka’s conversion and subsequent patronage were instrumental in elevating Buddhism from a localized tradition to a major spiritual force with a lasting impact on the cultural and religious landscape of Asia. His legacy continues to be felt in the widespread presence and influence of Buddhism around the world.

Buddhism in Central Asia

The spread of Buddhism into Central Asia is a fascinating chapter in the history of the religion, highlighting the role of trade, cultural exchange, and political patronage in the transmission of spiritual ideas. As the Silk Road—an extensive network of trade routes connecting the East and West—developed from the 2nd century BCE onwards, it facilitated not only the exchange of goods but also the movement of people, ideas, and religious traditions. Buddhism was among the major religions that traveled along these routes, gradually making its way into regions such as Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan.

Central Asia, with its diverse cultures and strategic location, served as a critical conduit through which Buddhism spread from India to China and beyond. The region’s role in this transmission was not merely passive; it was also an area where Buddhism took root, developed distinct characteristics, and contributed to the broader Buddhist cultural and artistic heritage.

(Early Introduction of Buddhism in Central Asia)

The earliest introduction of Buddhism into Central Asia likely occurred around the 2nd century BCE, coinciding with the expansion of the Mauryan Empire and the establishment of the Silk Road. As Buddhist monks and missionaries traveled along these routes, they carried with them Buddhist texts, teachings, and relics, establishing monastic communities and centers of learning in various Central Asian cities.

One of the earliest and most significant centers of Buddhism in Central Asia was the region of Bactria, corresponding to modern-day northern Afghanistan and southern Uzbekistan. Bactria was a crossroads of cultures and a melting pot of Hellenistic, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian influences. It was here that Buddhist communities first took hold, with monks establishing monasteries and stupas that served both as religious sites and as places of refuge and education for travelers along the Silk Road.

(The Kushan Empire and the Flourishing of Buddhism)

The spread and flourishing of Buddhism in Central Asia were significantly bolstered by the patronage of the Kushan Empire, which ruled large parts of Central Asia and northern India from the 1st to the 3rd centuries CE. The Kushans, originally a nomadic tribe from the Yuezhi confederation, adopted Buddhism as one of their state religions, and their empire became a major center for Buddhist learning and art.

The most notable Kushan ruler, King Kanishka (reigned approximately 127–151 CE), is often credited with playing a pivotal role in the spread of Buddhism. Kanishka’s reign marked a golden age for Buddhism in Central Asia. He is remembered for his patronage of Buddhist institutions, the construction of monumental stupas and monasteries, and his support for the compilation of Buddhist scriptures. The Fourth Buddhist Council, which was held in Kashmir during Kanishka’s reign, played a crucial role in codifying Buddhist teachings and promoting the spread of Mahayana Buddhism.

Under Kanishka’s patronage, the city of Gandhara (in present-day Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan) became a major center of Buddhist art and learning. The Gandhara region, which was part of the Kushan Empire, is famous for its unique artistic style that blended Hellenistic, Persian, and Indian influences to create some of the earliest iconic images of the Buddha. The Gandharan art style had a profound impact on the development of Buddhist art across Central Asia, China, and beyond, with its realistic representations of the Buddha and bodhisattvas influencing artistic traditions for centuries.

(Buddhism Along the Silk Road)

The Silk Road played a vital role in the transmission of Buddhism from Central Asia to China and eventually to Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Buddhist monks traveled with merchant caravans, bringing with them sacred texts, relics, and images of the Buddha. These monks established monasteries and stupas in key trading cities along the Silk Road, such as Merv (in modern-day Turkmenistan), Samarkand (in Uzbekistan), and Khotan (in present-day Xinjiang, China).

These monasteries served as cultural and intellectual hubs where Buddhist teachings were translated into various languages, including Sogdian, Tocharian, and Chinese. Central Asian translators and scholars played a crucial role in this process, helping to adapt Buddhist doctrines to the cultural and linguistic contexts of the regions they reached. The spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road was not just a religious phenomenon but also a catalyst for the exchange of knowledge, art, and technology between different civilizations.

(The Decline of Buddhism in Central Asia)

While Buddhism flourished in Central Asia for several centuries, it eventually began to decline due to various factors, including the rise of Islam in the region during the 7th and 8th centuries CE. As Islamic empires expanded into Central Asia, many Buddhist monasteries were abandoned, and the region’s Buddhist heritage was gradually forgotten. However, the impact of Buddhism on Central Asian culture, art, and history remains significant.

Despite its decline, the legacy of Buddhism in Central Asia is still visible today in the form of archaeological sites, such as the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, the remains of monasteries in Termez, Uzbekistan, and the ruins of Buddhist stupas in Merv, Turkmenistan. These sites, though often in ruins, testify to the once-thriving Buddhist communities that played a vital role in the religious and cultural history of the region.

(Summary)

Buddhism’s spread into Central Asia was a complex and multifaceted process, driven by the interconnectedness of ancient trade routes and the patronage of powerful empires like the Kushans. Central Asia was not only a bridge between India and China but also a vibrant center of Buddhist culture in its own right. The region’s contributions to Buddhist art, thought, and scholarship had a lasting impact on the development of Buddhism across Asia. Although Buddhism eventually waned in Central Asia, its influence can still be seen in the region’s historical and cultural landscape, offering a glimpse into a time when the teachings of the Buddha resonated across vast expanses of land, shaping the spiritual and artistic heritage of multiple civilizations.

Buddhism in China

Buddhism’s arrival in China is one of the most significant cultural and religious developments in the history of East Asia. Although Buddhism first entered China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), it began to gain significant traction only in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The transmission of Buddhism from India to China was a complex and multifaceted process, involving not only the physical movement of monks and texts but also a profound cultural exchange that led to the adaptation and reinterpretation of Buddhist teachings within the Chinese context.

(Early Introduction and Challenges)

The earliest references to Buddhism in China date back to the Han Dynasty, with historical records suggesting that Buddhist missionaries from Central Asia and India began to arrive in China around the 1st century CE. These early missionaries were likely traveling along the Silk Road, which facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and religious practices between China and the regions to its west. However, Buddhism faced significant challenges in its early days in China, as it was a foreign religion with concepts and practices that were initially unfamiliar and often at odds with traditional Chinese beliefs.

Confucianism and Daoism were the dominant intellectual and religious traditions in China at the time. Confucianism, with its emphasis on social order, filial piety, and moral ethics, and Daoism, with its focus on harmony with nature and the pursuit of immortality, formed the bedrock of Chinese thought. In contrast, Buddhism introduced ideas such as the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, karma, rebirth, and the concept of Nirvana, which were initially difficult for the Chinese to reconcile with their existing worldview.

Despite these challenges, Buddhism began to take root in China, particularly among those seeking alternatives to the established traditions. The religion’s emphasis on personal salvation, its sophisticated philosophical doctrines, and its monastic lifestyle attracted a growing number of followers. Over time, Buddhism started to influence various aspects of Chinese culture, including art, literature, and philosophy.

(The Role of Translation and Adaptation)

The spread of Buddhism in China was significantly aided by the translation of Indian Buddhist texts into Chinese. This process of translation was not merely linguistic; it involved a deep cultural exchange, as translators worked to render complex Buddhist concepts in a way that was accessible and meaningful to the Chinese audience. The early translators faced numerous challenges, such as finding equivalents for Sanskrit terms that had no direct counterparts in Chinese and conveying ideas that were foreign to Chinese thought.

Several key figures played pivotal roles in this translation effort. One of the most important was the monk Kumarajiva (344–413 CE), a renowned scholar who was born in the region of Kucha, a Buddhist kingdom on the Silk Road. Kumarajiva was brought to China in the early 5th century, where he led a major translation project in the capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an). He and his team of scholars translated many of the most important Mahayana Buddhist texts, including the Lotus Sutra, the Diamond Sutra, and the Vimalakirti Sutra. Kumarajiva’s translations were highly influential and are still regarded as some of the finest in the Chinese Buddhist canon. His work not only made Buddhist teachings more accessible to the Chinese but also shaped the development of Chinese Buddhism by emphasizing certain Mahayana concepts, such as the bodhisattva ideal and the doctrine of emptiness.

The process of adaptation was also critical to the acceptance of Buddhism in China. As Buddhist ideas spread, they were interpreted and integrated into the existing Chinese cultural and philosophical frameworks. For example, the concept of karma and rebirth was often understood in terms of Chinese notions of moral causality and ancestor worship, while the Buddhist monastic system was compared to the Daoist tradition of hermit sages. This syncretism helped Buddhism gain broader acceptance among the Chinese populace.

(Flourishing of Buddhism During the Tang Dynasty)

Buddhism reached its zenith in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), a period often regarded as the golden age of Chinese Buddhism. The Tang emperors, particularly Emperor Taizong and Empress Wu Zetian, were strong supporters of Buddhism, which led to the flourishing of Buddhist culture and the establishment of numerous temples, monasteries, and schools.

During the Tang period, Buddhism became deeply integrated into Chinese society and culture. Major Buddhist pilgrimage sites, such as Mount Wutai and Mount Emei, became popular destinations for devotees. The construction of grand temples, such as the Shaolin Temple, which was originally founded during the Northern Wei Dynasty but gained prominence during the Tang, showcased the importance of Buddhism in Chinese religious life. The Tang Dynasty also saw the emergence of Chinese Buddhist schools that developed distinct teachings and practices, adapting Indian Buddhism to the Chinese context.

One of the most significant developments during this period was the rise of Chan Buddhism, known as Zen in Japan. Chan Buddhism emphasized direct, experiential realization of the Buddha-nature inherent in all beings, often through meditation (zazen) and the use of paradoxical sayings or koans to transcend ordinary thinking. Chan masters like Bodhidharma, who is traditionally credited with bringing Chan Buddhism to China in the 5th or 6th century, and later figures like Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch, played crucial roles in shaping the school’s teachings. Chan Buddhism’s emphasis on simplicity, discipline, and direct experience resonated deeply with Chinese culture and had a lasting impact on East Asian spirituality.

Another important school that emerged during the Tang Dynasty was Pure Land Buddhism, which focused on devotion to Amitabha Buddha and the aspiration to be reborn in the Pure Land, a paradise where enlightenment could be more easily attained. Pure Land Buddhism became immensely popular among the lay population due to its accessible practices, such as reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha (nianfo), and its promise of salvation.

(Buddhism and the Arts)

The influence of Buddhism on Chinese art and literature was profound. Buddhist themes inspired countless works of art, including sculptures, paintings, and murals. The caves of Dunhuang and Yungang, filled with intricate carvings, frescoes, and statues, stand as magnificent testaments to the artistic achievements inspired by Buddhism in China. These artistic endeavors not only depicted scenes from the Buddha’s life and various Buddhist deities but also served as vehicles for the transmission of Buddhist teachings.

Buddhism also contributed to the development of Chinese literature, particularly through the creation of religious poetry and prose that reflected Buddhist philosophy and ethics. The integration of Buddhist concepts into Chinese poetry, especially during the Tang Dynasty, enriched the literary tradition and left a lasting legacy in Chinese cultural history.

(Buddhism’s Influence and Decline)

The influence of Buddhism in China extended beyond religion and culture; it also played a role in shaping Chinese philosophy, ethics, and governance. The Buddhist concept of compassion and the bodhisattva ideal influenced the development of social welfare practices, while the monastic system provided education and refuge for many.

However, the prominence of Buddhism in China also led to periods of tension and persecution, particularly during times when the state sought to reassert control over religious institutions. The most notable instance of persecution occurred during the reign of Emperor Wuzong of the Tang Dynasty, who launched the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution in 845 CE. Thousands of monasteries were destroyed, and monks and nuns were forced to return to lay life. Despite this setback, Buddhism remained a vital part of Chinese spiritual life and continued to influence other East Asian cultures.

(Summary)

The transmission of Buddhism to China was a complex and transformative process that involved much more than the simple adoption of a foreign religion. Through centuries of translation, adaptation, and synthesis with indigenous Chinese traditions, Buddhism became deeply embedded in Chinese culture, philosophy, and art. The Tang Dynasty marked the height of Buddhism’s influence in China, with the development of distinctive Chinese Buddhist schools like Chan and Pure Land. Although Buddhism in China experienced periods of decline, its legacy remains evident in the continued practice of Buddhism, the influence on Chinese thought, and the enduring presence of Buddhist art and architecture across the country.

Buddhism in Korea and Japan

Buddhism’s spread from China to Korea and Japan marked a significant expansion of the religion across East Asia, where it continued to adapt and evolve within new cultural contexts. Both Korea and Japan not only adopted Buddhism but also made unique contributions to its development, shaping distinct forms of the religion that remain influential to this day.

(Buddhism in Korea)

Buddhism was introduced to Korea during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE – 668 CE), a time when the Korean Peninsula was divided into three rival kingdoms: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. The arrival of Buddhism in Korea was closely linked to the cultural and political exchanges between Korea and China.

Goguryeo: The kingdom of Goguryeo was the first to receive Buddhism, traditionally in 372 CE, when the Chinese monk Sundo arrived at the Goguryeo court with Buddhist texts and images. Buddhism was initially embraced by the royal family and the aristocracy, who saw it as a means of strengthening the state and legitimizing their rule. Over time, Buddhism spread among the populace, supported by the construction of temples and the establishment of monastic communities.

Baekje: The kingdom of Baekje received Buddhism shortly after Goguryeo, with the arrival of the monk Marananta from Eastern Jin China in 384 CE. Baekje’s rulers quickly adopted Buddhism, and the religion became closely associated with the state. Baekje played a crucial role in transmitting Buddhism to Japan, as many Korean monks, artisans, and scholars traveled to Japan, carrying with them Buddhist teachings, texts, and art.

Silla: The kingdom of Silla was the last of the three kingdoms to officially adopt Buddhism, in 528 CE. Buddhism in Silla initially faced resistance from conservative elements within the court, but it eventually became the state religion, especially after the unification of the Korean Peninsula under Silla in 668 CE. Silla became a major center of Buddhist learning, with famous temples like Hwangnyongsa and Bulguksa being constructed during this period. Korean monks from Silla, such as Wonhyo and Uisang, made significant contributions to the development of Korean Buddhist philosophy, particularly through their interpretations of Mahayana Buddhism.

The unification of Korea under Silla allowed Buddhism to flourish across the entire peninsula, leading to the establishment of the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392 CE), during which Buddhism became deeply integrated into Korean society. The Goryeo period saw the creation of the Tripitaka Koreana, a comprehensive collection of Buddhist scriptures carved onto over 80,000 woodblocks, which remains one of the most complete and accurate versions of the Buddhist canon.

(Unique Contributions of Korean Buddhism)

Korean Buddhism developed several distinctive characteristics, including the emphasis on Seon (Zen) meditation and the integration of various Buddhist schools. Seon Buddhism, which emphasizes meditation and direct experience of enlightenment, became particularly influential during the later periods of Korean history. Korean monks also engaged in doctrinal synthesis, bringing together different strands of Buddhist thought into cohesive systems, a practice exemplified by the works of the monk Wonhyo.

Another significant contribution of Korean Buddhism was the close relationship between Buddhism and the state. Korean rulers frequently supported Buddhism as a means of consolidating political power, using Buddhist ceremonies and symbols to legitimize their authority. The construction of massive temple complexes and the patronage of Buddhist art and scholarship were common practices among Korean monarchs.

Despite facing challenges such as Confucian opposition during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897 CE), Buddhism has remained a vital part of Korean culture. Modern Korean Buddhism continues to be a major religious force, with traditions such as Jogye and Taego remaining prominent.

(Buddhism in Japan)

Buddhism was officially introduced to Japan in the mid-6th century CE during the Asuka period (538–710 CE), a time when the Japanese islands were beginning to form a more centralized state. The introduction of Buddhism to Japan is traditionally dated to 552 CE, when a delegation from the Korean kingdom of Baekje presented the Japanese court with a gilded Buddha statue, Buddhist scriptures, and other ritual objects as a diplomatic gift.

Initial Resistance and Acceptance: The initial reception of Buddhism in Japan was mixed. While some members of the Japanese court, particularly the powerful Soga clan, embraced Buddhism, others, including the conservative Mononobe clan, opposed it, fearing that the foreign religion might offend the native kami (Shinto deities) and undermine traditional beliefs. This tension led to a series of conflicts within the court, but eventually, Buddhism gained acceptance, especially with the support of influential figures like Prince Shōtoku (574–622 CE).

Prince Shōtoku: Prince Shōtoku is often credited with playing a pivotal role in the early promotion and spread of Buddhism in Japan. As a regent and a statesman, Shōtoku was a devout Buddhist who saw the religion as a means of promoting social harmony and unifying the country. He is traditionally attributed with the establishment of the Seventeen-Article Constitution, which, while primarily Confucian, also reflects Buddhist principles of ethics and governance. Shōtoku also founded several important temples, including Horyu-ji, one of the oldest wooden structures in the world, which became a center for Buddhist learning and culture.

Nara Period (710–794 CE): The Nara period marked the establishment of Buddhism as a state religion in Japan. The Japanese government, under the influence of the powerful Fujiwara clan, built numerous temples and sponsored the creation of Buddhist art and texts. The Great Buddha statue (Daibutsu) at Todai-ji temple in Nara, which was commissioned by Emperor Shomu, is one of the most famous symbols of this era. Buddhism during the Nara period was closely tied to the state, with the government using Buddhist rituals to ensure the prosperity and protection of the nation.

Heian Period (794–1185 CE): During the Heian period, Buddhism in Japan continued to develop, with the emergence of new schools and practices. Two of the most influential schools were Tendai and Shingon Buddhism, both of which were introduced by Japanese monks who had studied in China. Tendai, founded by Saicho, emphasized the teachings of the Lotus Sutra and the idea that all beings have the potential for Buddhahood. Shingon, founded by Kukai (also known as Kobo Daishi), focused on esoteric practices, including mantras, mudras, and mandalas, and was associated with the syncretic integration of Buddhism and native Japanese beliefs.

(Development of Unique Japanese Buddhist Schools)

As Buddhism took root in Japan, it evolved into unique forms that reflected the cultural and spiritual landscape of the country. Two of the most prominent schools that emerged during the medieval period were Pure Land Buddhism and Zen Buddhism.

Pure Land Buddhism: Pure Land Buddhism became one of the most popular forms of Buddhism in Japan, particularly among the common people. It was introduced by the monk Honen in the late 12th century and emphasized devotion to Amida Buddha, with the belief that reciting the Nembutsu (the name of Amida Buddha) with sincere faith would ensure rebirth in the Pure Land, a paradise where enlightenment could be more easily attained. Honen’s disciple, Shinran, further developed these ideas and founded the Jodo Shinshu (True Pure Land) school, which became one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

Zen Buddhism: Zen Buddhism, derived from the Chan tradition of China, was introduced to Japan by monks like Eisai and Dogen in the 12th and 13th centuries. Zen emphasizes direct, experiential practice, particularly through meditation (zazen), and often rejects reliance on scriptures and rituals. Zen teachings stress the importance of realizing one’s Buddha-nature through disciplined practice, often using koans (paradoxical riddles) to transcend conventional thinking. Zen Buddhism became particularly influential among the samurai class, and its aesthetic principles deeply influenced Japanese culture, including the tea ceremony, garden design, and the martial arts.

(Buddhism’s Influence and Legacy in Korea and Japan)

In both Korea and Japan, Buddhism became deeply integrated into the fabric of society, influencing everything from politics and philosophy to art and literature. The construction of temples and monasteries, the creation of Buddhist sculptures and paintings, and the composition of religious texts all reflect the profound impact of Buddhism on the cultural heritage of these countries.

In Korea, despite periods of suppression, Buddhism has remained a major religious tradition, with its temples and monastic practices continuing to play a significant role in the spiritual lives of many Koreans. In Japan, Buddhism coexists with Shinto, the indigenous religion, in a unique syncretic relationship where many Japanese people engage in both Buddhist and Shinto practices.

Today, the legacy of Buddhism in Korea and Japan is evident in the continued practice of various Buddhist traditions, the preservation of ancient temples and art, and the ongoing influence of Buddhist philosophy on East Asian culture. Zen Buddhism, in particular, has gained international recognition and has had a profound influence on global spirituality and the arts.

(Summary)

The spread of Buddhism from China to Korea and Japan marked a significant expansion of the religion and led to the development of unique forms of Buddhism that adapted to the cultural and spiritual contexts of these countries. In Korea, Buddhism became deeply intertwined with the state and society, influencing everything from governance to art. In Japan, Buddhism evolved into distinct schools such as Pure Land and Zen, which have had a lasting impact on Japanese culture and spirituality. The transmission and adaptation of Buddhism in Korea and Japan highlight the dynamic nature of the religion and its ability to resonate across different cultures and historical periods.

Buddhism in Southeast Asia

Buddhism’s spread to Southeast Asia marked a significant chapter in the religion’s history, influencing the cultural, religious, and political landscapes of the region. Buddhism arrived in Southeast Asia through a combination of maritime trade routes and the missionary efforts of monks and traders. By the 3rd century BCE, Theravada Buddhism had already reached Sri Lanka, which became a major center for the dissemination of Buddhist teachings to other parts of Southeast Asia.

(Early Introduction and Spread)

Sri Lanka as a Hub of Theravada Buddhism: Buddhism is believed to have been introduced to Sri Lanka during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa (247–207 BCE) by Mahinda, the son of Emperor Ashoka of India. Mahinda’s mission to Sri Lanka, which was part of Ashoka’s broader effort to promote Buddhism beyond India, laid the foundation for the establishment of Theravada Buddhism in Sri Lanka. The religion quickly took root and became the dominant spiritual tradition on the island, with the construction of monasteries, stupas, and the establishment of a monastic order.

Sri Lanka’s pivotal role as a center for Theravada Buddhism led to the spread of the tradition to other regions of Southeast Asia. Monks from Sri Lanka traveled to various parts of the region, carrying with them the Pali Canon and other essential Buddhist texts, which helped to solidify Theravada Buddhism’s influence in Southeast Asia.

Burma (Myanmar): Theravada Buddhism was introduced to Burma (modern-day Myanmar) around the 5th century CE, although there may have been earlier Buddhist influences through contact with India and Sri Lanka. The Mon people, an ethnic group in Lower Burma, were among the earliest adopters of Theravada Buddhism. The construction of temples and monasteries, such as those in the ancient city of Bagan, marked the growing influence of Buddhism in the region. By the 11th century, under the reign of King Anawrahta (1044–1077 CE), Theravada Buddhism was established as the state religion of the Pagan Kingdom, leading to the flourishing of Buddhist culture and the construction of thousands of pagodas across the kingdom.

Thailand: Buddhism was introduced to Thailand through multiple waves of cultural exchange, primarily from Sri Lanka and India. The earliest evidence of Buddhism in Thailand dates back to the 3rd century BCE, but it was during the Sukhothai Kingdom (13th–15th centuries CE) that Theravada Buddhism became the dominant religion. King Ramkhamhaeng, one of the most famous rulers of Sukhothai, played a crucial role in promoting Theravada Buddhism, establishing it as the state religion and integrating it into the cultural fabric of Thai society. The influence of Buddhism is evident in the art, architecture, and literature of the Sukhothai and later Ayutthaya Kingdoms.

Laos: Buddhism was introduced to Laos around the 8th century CE, likely through contact with neighboring regions like Thailand and Cambodia. However, it wasn’t until the 14th century, during the reign of King Fa Ngum, the founder of the Kingdom of Lan Xang, that Theravada Buddhism became firmly established as the state religion. Fa Ngum’s adoption of Theravada Buddhism was influenced by his close ties with the Khmer Empire, which was already a center of Theravada Buddhist practice. Monasteries and temples were built throughout the kingdom, and the religion became deeply ingrained in the daily lives of the Lao people.

Cambodia: Buddhism’s history in Cambodia is marked by a complex interplay of religious influences, including Hinduism, Mahayana Buddhism, and later, Theravada Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism were the dominant religions during the early centuries of the Khmer Empire (9th–15th centuries CE). The famous temple complex of Angkor Wat, initially dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu, was later converted into a Buddhist temple as Mahayana Buddhism gained prominence.

Over time, however, Theravada Buddhism began to spread from Sri Lanka and Thailand to Cambodia. By the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism had supplanted Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism as the dominant religious tradition in Cambodia. The transition was largely peaceful, and the new form of Buddhism was readily adopted by the Khmer people, shaping Cambodian religious practices to this day. The influence of Theravada Buddhism is evident in the architecture of later Khmer temples, which reflect the simpler, more austere style associated with Theravada practice.

(Syncretism and Adaptation)

In Southeast Asia, Buddhism did not exist in isolation but instead blended with local animist and Hindu practices, creating unique forms of Buddhist worship and cultural expression. This syncretism allowed Buddhism to be more readily accepted by local populations, who could incorporate the new teachings into their existing religious frameworks.

Animism: In many parts of Southeast Asia, local animist beliefs that focused on the worship of spirits (nats in Burma, phi in Thailand, etc.) were integrated into Buddhist practices. For example, in Myanmar, it is common to find shrines dedicated to nats alongside Buddhist stupas, and rituals often involve offerings to both the Buddha and local spirits. This blending of beliefs has resulted in a form of Buddhism that is deeply intertwined with the indigenous spiritual practices of the region.

Hinduism: Hinduism had a significant influence on the early religious landscape of Southeast Asia, particularly in the Khmer Empire, where Hindu deities and cosmology were central to royal rituals and temple architecture. As Buddhism spread, it often absorbed elements of Hinduism, leading to the coexistence of Buddhist and Hindu symbols and practices. For instance, the Buddhist concept of the bodhisattva was sometimes merged with Hindu deities, and Hindu epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata continued to be popular in Buddhist-majority regions.

(The Khmer Empire and the Transition to Theravada Buddhism)

The Khmer Empire (9th–15th centuries CE) in Cambodia is one of the most notable examples of the interplay between Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Initially, the Khmer rulers were patrons of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, which is reflected in the grandeur of temples like Angkor Wat and Bayon. These temples served as centers of religious and political power, where the king was often seen as a divine ruler connected to the gods.

However, by the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism began to gain prominence in the Khmer Empire, eventually becoming the dominant religious tradition. This shift was likely influenced by the spread of Theravada Buddhism from Sri Lanka and Thailand, as well as the growing appeal of its teachings, which were more accessible to the general population. Unlike Mahayana Buddhism, which was often associated with the elite, Theravada Buddhism emphasized the individual’s path to enlightenment through ethical living, meditation, and devotion, making it more relatable to the common people.

The transition from Mahayana to Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia was marked by a change in religious practices and temple architecture. Temples became simpler in design, reflecting the Theravada focus on personal meditation and devotion rather than the elaborate rituals associated with Mahayana and Hindu worship. This transformation had a lasting impact on Cambodian culture, and Theravada Buddhism remains the predominant form of Buddhism in Cambodia today.

(Buddhism’s Influence and Legacy in Southeast Asia)

Buddhism has played a central role in shaping the cultural, social, and political landscapes of Southeast Asia. The religion’s emphasis on ethics, meditation, and community service has influenced the moral and spiritual values of the region, while Buddhist temples and monasteries have served as centers of learning, art, and social welfare.

In countries like Thailand and Myanmar, Buddhism is deeply intertwined with national identity, and the Sangha (the Buddhist monastic community) continues to hold significant influence in both religious and secular matters. Festivals, rituals, and ceremonies based on the Buddhist calendar are integral to the cultural life of these nations, and Buddhist teachings continue to guide social norms and practices.

The artistic legacy of Buddhism in Southeast Asia is also profound. The region is home to some of the world’s most impressive Buddhist monuments, including the temple complexes of Bagan in Myanmar, the ancient city of Ayutthaya in Thailand, and the Angkor temples in Cambodia. These sites not only serve as places of worship but also as symbols of the enduring legacy of Buddhism in Southeast Asia.

In modern times, Buddhism in Southeast Asia faces challenges, including the pressures of modernization, secularization, and political conflicts. However, the religion remains a vital part of the region’s cultural heritage, with millions of people continuing to practice Buddhism and draw inspiration from its teachings.

(Summary)

Buddhism’s spread to Southeast Asia was a transformative process that led to the creation of distinct forms of the religion that are still practiced today. Through a combination of trade, missionary work, and cultural exchange, Theravada Buddhism became deeply rooted in countries like Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, while also blending with local animist and Hindu traditions. The Khmer Empire’s transition from Mahayana to Theravada Buddhism is a key example of how Buddhism adapted to local contexts, leading to lasting cultural and religious changes. Today, Buddhism continues to be a major spiritual force in Southeast Asia, shaping the region’s cultural identity and influencing the lives of millions.

Buddhism in Tibet

Buddhism’s arrival in Tibet during the 7th century CE marked the beginning of a profound transformation in Tibetan culture, spirituality, and society. This introduction occurred under the reign of King Songtsen Gampo, a powerful ruler who played a crucial role in establishing Buddhism as the dominant religion in Tibet. His reign, combined with the efforts of later Tibetan rulers and spiritual leaders, helped Buddhism take root in the region, where it developed into a unique form known as Tibetan Buddhism.

(The Introduction of Buddhism to Tibet)

King Songtsen Gampo and the Royal Marriages: King Songtsen Gampo (604–650 CE) is often credited with introducing Buddhism to Tibet. His strategic marriages to two Buddhist princesses—Bhrikuti from Nepal and Wencheng from China—were instrumental in bringing Buddhist teachings and practices to Tibet. These marriages not only strengthened political alliances but also facilitated the transmission of Buddhist culture and iconography to Tibet.

Both queens brought with them sacred Buddhist texts, images, and relics, which were enshrined in newly constructed temples in Lhasa, such as the Jokhang and Ramoche temples. These temples became centers for the practice and propagation of Buddhism, marking the beginning of the religion’s spread in Tibet. Songtsen Gampo himself is considered an emanation of Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig in Tibetan), the bodhisattva of compassion, which further solidified the connection between the Tibetan royal family and the Buddhist faith.

Early Challenges and Syncretism: Initially, Buddhism faced significant challenges in gaining a foothold in Tibet, as the indigenous Bon religion was deeply entrenched in Tibetan society. Bon, which predated Buddhism in Tibet, was a shamanistic and animistic tradition that emphasized rituals to appease spirits and deities associated with nature. Rather than outright replacing Bon, Buddhism in Tibet evolved by incorporating many elements of Bon, leading to a unique synthesis of religious practices and beliefs. This process of syncretism allowed Buddhism to resonate more deeply with the Tibetan people and facilitated its acceptance.

(The Role of Padmasambhava and the Establishment of Tibetan Buddhism)

Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche): One of the most significant figures in the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet was Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche. A legendary tantric master from the Indian subcontinent, Padmasambhava was invited to Tibet by King Trisong Detsen (reigned c. 755–797 CE) in the 8th century CE to help overcome obstacles to the spread of Buddhism, particularly resistance from the indigenous Bon practitioners.

Padmasambhava’s influence on Tibetan Buddhism cannot be overstated. He is credited with subduing local spirits and deities, converting them into protectors of the Dharma (Buddhist teachings). Through his mastery of tantric practices and rituals, Padmasambhava established the foundations of Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet, which emphasized esoteric teachings, meditation, and the use of mantras, mudras, and mandalas. His teachings were codified in the Nyingma school, the oldest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Padmasambhava is revered as the “Second Buddha” in Tibet, and his teachings continue to be central to Tibetan spiritual practice.

Translation of Buddhist Texts: Another critical aspect of Buddhism’s establishment in Tibet was the translation of Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit and other languages into Tibetan. This monumental task was undertaken by Tibetan scholars and Indian Buddhist masters who worked together to translate the vast corpus of Buddhist texts, including sutras, tantras, and commentaries. The Tibetan translation of these texts, known as the Kangyur (the words of the Buddha) and the Tengyur (commentaries by Indian and Tibetan scholars), became the foundation of Tibetan Buddhist literature and education.

The translation efforts were supported by Tibetan kings, most notably King Trisong Detsen, who also founded the Samye Monastery, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. Samye became a center of learning, where Tibetan monks were trained in Buddhist philosophy, rituals, and meditation practices. The establishment of monasteries like Samye played a crucial role in the institutionalization of Buddhism in Tibet and its spread across the region.

(Development and Spread of Tibetan Buddhism)

Formation of Tibetan Buddhist Schools: Over the centuries, Tibetan Buddhism developed into several distinct schools, each with its own teachings, practices, and lineages. The four main schools are the Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug. Each school contributed to the rich tapestry of Tibetan Buddhist thought and practice, with a focus on various aspects of tantric Buddhism, scholasticism, and meditation.

- Nyingma: The oldest school, founded on the teachings of Padmasambhava, emphasizes the Dzogchen (Great Perfection) teachings, which focus on recognizing the intrinsic nature of mind as pure and luminous.

- Kagyu: Known for its emphasis on meditation and the practice of Mahamudra (the Great Seal), which teaches the direct experience of the nature of mind.

- Sakya: This school is noted for its scholarly tradition and the Lamdre (Path and Result) teachings, which provide a comprehensive path to enlightenment.

- Gelug: Founded by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419 CE), the Gelug school is the most recent and became the most politically influential. The Dalai Lama, the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet, belongs to this school.

The Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism: The institution of the Dalai Lama, established in the 15th century, became a central feature of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama is considered the reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara and serves as both the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and the political leader of Tibet. The current Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is the 14th in the line of succession and has been instrumental in promoting Tibetan Buddhism and culture worldwide, particularly after the Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959.

Expansion Beyond Tibet: Tibetan Buddhism did not remain confined to Tibet. It spread to neighboring regions, including Bhutan, Mongolia, Ladakh (northern India), and parts of China. In Bhutan, Tibetan Buddhism became the state religion, and the Drukpa Kagyu school became the dominant tradition. In Mongolia, Tibetan Buddhism was introduced in the 13th century and became the dominant religion under the influence of the Gelug school. The Mongolian rulers, particularly during the reign of Altan Khan, established close ties with the Tibetan lamas, leading to the widespread adoption of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia.

(Influence of Tibetan Buddhism on Culture and Society)

Tibetan Buddhism has had a profound impact on the culture, art, and society of Tibet and the surrounding regions. The religion’s emphasis on compassion, non-violence, and the pursuit of enlightenment has shaped the moral and ethical values of Tibetan society. Tibetan monasteries have traditionally served as centers of learning, not only for religious education but also for the study of medicine, astrology, and the arts.

Art and Architecture: Tibetan Buddhist art is renowned for its intricate thangkas (religious paintings), mandalas (spiritual symbols representing the universe), and statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. The construction of monasteries and stupas, often located in remote and mountainous regions, reflects the deep spiritual significance of these structures. The Potala Palace in Lhasa, the former residence of the Dalai Lama, is one of the most iconic examples of Tibetan Buddhist architecture.

Literature and Philosophy: Tibetan Buddhism has also produced a vast body of literature, including commentaries on Buddhist texts, philosophical treatises, and spiritual biographies of revered lamas. The study of Buddhist philosophy, particularly the teachings of Madhyamaka (the Middle Way) and Pramana (Buddhist logic and epistemology), has been central to Tibetan monastic education.

(Modern Challenges and Global Influence)

In the modern era, Tibetan Buddhism has faced significant challenges, particularly following the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950 and the subsequent suppression of religious practices. The 14th Dalai Lama’s exile in 1959 and the destruction of many monasteries during the Cultural Revolution in China had a profound impact on Tibetan Buddhism. Despite these challenges, Tibetan Buddhism has experienced a global renaissance, with Tibetan lamas establishing monasteries and teaching centers around the world. The Dalai Lama’s message of compassion and non-violence has resonated with people from diverse cultural backgrounds, contributing to the global spread of Tibetan Buddhism.

Today, Tibetan Buddhism continues to thrive both within and outside Tibet. It remains a vital part of Tibetan cultural identity and has gained a significant following among Western practitioners, who are drawn to its teachings on meditation, mindfulness, and the pursuit of inner peace.

(Summary)

Buddhism’s introduction to Tibet in the 7th century CE marked the beginning of a profound spiritual journey that transformed the region’s culture, society, and religious landscape. Through the efforts of key figures like King Songtsen Gampo, Padmasambhava, and later Tibetan lamas, Buddhism became deeply rooted in Tibet, evolving into a unique tradition known as Tibetan Buddhism. Despite facing significant challenges in the modern era, Tibetan Buddhism continues to influence and inspire people worldwide, preserving its rich heritage and teachings for future generations.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The spread of Buddhism across Asia left an indelible mark on the cultural, social, and intellectual landscapes of the regions it touched. From its origins in India, Buddhism traveled across the continent, deeply influencing art, architecture, literature, and philosophy in countries such as China, Japan, Korea, Tibet, and Southeast Asia. The cultural legacy of Buddhism is vast, shaping not only religious practices but also the everyday lives and governance of people throughout Asia.

(Influence on Art and Architecture)

Stupas, Pagodas, and Monasteries: One of the most visible cultural impacts of Buddhism is its influence on architecture. As Buddhism spread, the construction of stupas—dome-shaped structures containing relics of the Buddha or other significant figures—became a common practice. Stupas served as focal points for religious worship and pilgrimage, and their design evolved as Buddhism spread to different regions. For instance, in East Asia, stupas were transformed into pagodas, tall, multi-tiered towers that became iconic symbols of Buddhist architecture in countries like China, Japan, and Korea.

Buddhist monasteries also played a crucial role in shaping the architectural landscape. Monasteries were not only centers of religious practice but also hubs of education, art, and culture. The layout and design of these monasteries varied across regions, reflecting local architectural styles while adhering to the principles of Buddhist symbolism and cosmology. For example, the Jokhang Temple in Tibet, the Shaolin Temple in China, and the Todaiji Temple in Japan are all significant examples of how Buddhism influenced local architecture.

Buddhist Art and Iconography: The spread of Buddhism also gave rise to a rich tradition of religious art. Depictions of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and scenes from the Jataka tales (stories of the Buddha’s previous lives) became central themes in sculpture, painting, and mural art. The style and iconography of Buddhist art evolved as the religion spread, incorporating elements from local cultures and artistic traditions.

In India, the earliest depictions of the Buddha were aniconic, represented through symbols such as the Bodhi tree, the wheel of Dharma, and the footprints of the Buddha. However, with the rise of the Gandhara and Mathura schools of art during the Kushan Empire, the Buddha began to be depicted in human form, influenced by Greco-Roman artistic traditions. As Buddhism spread to China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, the depiction of the Buddha and other Buddhist figures was adapted to reflect the physical features and artistic sensibilities of these regions.

Mandala and Thangka Paintings: In Tibet, Buddhist art took on unique forms, with the creation of intricate mandalas—geometric representations of the universe used as aids in meditation—and thangkas, scroll paintings depicting deities, historical figures, and spiritual scenes. These art forms are not only visually striking but also serve as important tools for meditation and spiritual practice. The detailed symbolism in mandalas and thangkas reflects the complex cosmology and spiritual teachings of Tibetan Buddhism.

(Impact on Literature and Philosophy)

Buddhist Texts and Scholarly Tradition: The transmission of Buddhist teachings across Asia led to the development of a vast body of religious literature. Buddhist texts were originally composed in Pali and Sanskrit in India, but as Buddhism spread, these texts were translated into a multitude of languages, including Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, and Korean. The translation and preservation of these texts were monumental tasks undertaken by dedicated scholars and monks. For example, the Chinese monk Xuanzang traveled to India in the 7th century CE to collect Buddhist scriptures, which he later translated into Chinese, significantly enriching the Buddhist canon in East Asia.

Buddhism also contributed to the development of a scholarly tradition in many regions. Monasteries became centers of learning, where monks studied not only religious texts but also subjects such as philosophy, logic, medicine, and linguistics. The intellectual traditions of Buddhism, particularly the teachings of Madhyamaka (the Middle Way) and Yogacara (Consciousness-Only) schools, had a profound influence on the philosophical landscape of Asia. The debates and commentaries on Buddhist philosophy contributed to the development of a rich intellectual culture that extended beyond the confines of religion.

Literary and Poetic Contributions: In addition to philosophical texts, Buddhism inspired a wealth of literary and poetic works. The Jataka tales, recounting the past lives of the Buddha, became popular in many Buddhist countries and were adapted into local folklore and literature. In Japan, the influence of Buddhism can be seen in classical literature, such as the Tale of Genji and The Tale of the Heike, which explore themes of impermanence and the transient nature of life—central concepts in Buddhist thought.

Buddhism also influenced poetry, particularly in East Asia. The Japanese haiku, with its emphasis on simplicity, nature, and the present moment, reflects the influence of Zen Buddhism. Similarly, Chinese Buddhist poetry, often composed by monks, expresses themes of meditation, nature, and the pursuit of enlightenment.

(Ethical and Social Impact)

Compassion, Non-violence, and Social Responsibility: One of the core ethical teachings of Buddhism is the emphasis on compassion (karuna) and non-violence (ahimsa). These principles had a profound impact on the social and political fabric of the regions where Buddhism took root. For example, Emperor Ashoka of India, after converting to Buddhism, embraced non-violence and implemented policies promoting social welfare, animal rights, and religious tolerance. His edicts, inscribed on pillars and rocks across his empire, reflect the influence of Buddhist ethics on governance.

In other parts of Asia, Buddhist teachings on compassion and non-violence influenced social practices and attitudes toward war, justice, and the treatment of animals. The Buddhist concept of interdependence, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of all life, fostered a sense of social responsibility and community service. This is evident in the monastic tradition, where monks not only engaged in religious practice but also provided education, healthcare, and social services to the broader community.

Monastic Institutions and Education: Monasteries served as important social institutions in many Buddhist societies. In addition to being centers of religious practice, they functioned as schools, hospitals, and community centers. Monastic education was not limited to religious training; it often included instruction in various secular subjects, such as grammar, rhetoric, and medicine. In this way, Buddhist monastic institutions played a crucial role in the preservation and transmission of knowledge across generations.

In countries like Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Tibet, monastic education continues to be a vital part of the cultural and intellectual life. The role of monasteries in providing education and social services contributed to the overall development of these societies, fostering a sense of community and shared values based on Buddhist principles.

(Political Influence and Legacy)

Buddhism and Governance: In many regions, Buddhism significantly influenced political structures and ideologies. In Tibet, the merging of religious and political authority under the Dalai Lama exemplifies the close relationship between Buddhism and governance. Similarly, in Southeast Asia, Buddhist kingship became a central concept, where rulers were seen as dhammaraja, or righteous kings, who governed according to Buddhist principles.

In Japan, the influence of Buddhism on politics is evident in the adoption of the Seventeen-Article Constitution by Prince Shōtoku in the 7th century CE, which incorporated Buddhist ethics into the governance framework. Buddhism also played a role in shaping legal codes and justice systems in various Asian countries, emphasizing moral conduct, compassion, and the protection of life.

Buddhism’s Role in Modern Society: In the modern era, Buddhism continues to exert a significant cultural and ethical influence, both in Asia and globally. The teachings of Buddhism have inspired social and political movements, particularly in the areas of peace, environmentalism, and human rights. Figures like Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama have been prominent advocates for non-violence, compassion, and mindfulness, gaining worldwide recognition for their efforts to promote peace and social justice.

Buddhism’s emphasis on mindfulness and meditation has also gained widespread popularity in the West, influencing contemporary approaches to mental health, wellness, and personal development. The practice of mindfulness, derived from Buddhist meditation techniques, has been integrated into various therapeutic practices, contributing to a broader cultural shift towards holistic and mindful living.

(Summary)

The spread of Buddhism across Asia has left a lasting legacy that continues to shape the cultural, intellectual, and social landscapes of the regions it touched. From influencing art and architecture to shaping ethical values and political ideologies, Buddhism’s impact is both profound and enduring. As Buddhism continues to evolve and adapt to new contexts in the modern world, its teachings on compassion, mindfulness, and the interconnectedness of all life remain relevant, offering timeless insights and guidance for individuals and societies alike.

Conclusion,

The spread of Buddhism across Asia represents one of the most remarkable episodes in the history of global cultural exchange. From its humble beginnings in the Indian subcontinent, Buddhism embarked on a transformative journey that saw it penetrate and profoundly influence diverse regions and societies. The adaptation of Buddhism to various cultural contexts—from the introduction of the Middle Way in China to the integration with local traditions in Southeast Asia—illustrates its remarkable flexibility and enduring appeal.

The contributions of key historical figures, such as Emperor Ashoka, who played a pivotal role in propagating Buddhism across India and beyond, underscore the religion’s dynamic evolution. Ashoka’s support not only facilitated the construction of iconic stupas and monasteries but also spurred missionary activities that extended Buddhism’s reach into Central Asia, Sri Lanka, and further afield. Similarly, the assimilation of Buddhism into the cultural and spiritual landscapes of China, Korea, Japan, and Tibet highlights its ability to resonate with and adapt to diverse cultural settings.

As Buddhism continued to spread, it left an indelible impact on art, architecture, philosophy, and societal values across Asia. Its teachings on compassion, mindfulness, and the pursuit of enlightenment continue to inspire millions worldwide. The legacy of Buddhism’s expansion is evident in the rich tapestry of cultural and religious practices that have evolved over centuries, reflecting its profound influence on the spiritual and cultural heritage of Asia.

In sum, the journey of Buddhism across Asia is a testament to its universal message of inner peace and enlightenment. Its evolution and adaptation through different historical and cultural contexts not only showcase its resilience but also its ability to foster cross-cultural understanding and harmony. The enduring presence of Buddhism in various forms across Asia and its ongoing relevance in the modern world affirm the lasting significance of its teachings and its role in shaping the spiritual and cultural landscapes of diverse societies.