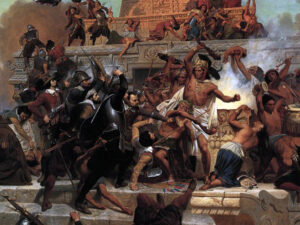

In the early 16th century, the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, led by Hernán Cortés, marked the beginning of a new era in the Americas. The Aztecs, with their impressive capital of Tenochtitlán, were a powerful and sophisticated civilization with advanced urban planning and a rich cultural heritage. However, the arrival of Cortés and his small band of conquistadors in 1519 set the stage for a dramatic confrontation. Over the next two years, through a combination of strategic alliances, fierce battles, and tactical ingenuity, the Spanish managed to topple one of the most formidable empires of the pre-Columbian world.

The fall of Tenochtitlán in 1521 was not just a military triumph but a profound cultural upheaval that heralded the dawn of Spanish colonization in the Americas. This conquest brought about a seismic shift in the region’s socio-political landscape, initiating an era of European influence that would dramatically reshape the continent. The interaction between the Spanish settlers and the indigenous peoples resulted in a complex legacy of both conflict and cultural exchange, setting the stage for centuries of transformation in the Americas.

(picryl.com)

Background: The Aztec Empire Before the Conquest

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Aztec Empire stood as one of the most formidable and sophisticated civilizations in the Americas. Emerging from humble beginnings in the early 14th century, the Aztecs, originally a nomadic tribe known as the Mexica, settled on the islands of Lake Texcoco, where they founded their capital, Tenochtitlán, in 1325. This city, located in what is now modern-day Mexico City, would become the heart of one of the largest and most influential empires in pre-Columbian America.

(The Rise of an Empire)

The growth of the Aztec Empire was fueled by a combination of military conquest, strategic alliances, and an intricate system of tribute. The Triple Alliance, formed in 1428 between Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan, marked a turning point in Aztec history. Together, these three city-states successfully overthrew the Tepanec rulers and began expanding their dominion across central Mexico. Over the next century, the Aztecs extended their influence over much of Mesoamerica, subjugating numerous city-states and regions, each required to pay tribute in the form of goods, labor, or military support.

(The Splendor of Tenochtitlán)

Tenochtitlán itself was a marvel of urban planning and engineering, boasting an estimated population of 200,000 to 300,000 at its height, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time. The city was built on a series of small islands connected by a network of causeways, canals, and bridges, which facilitated transportation and commerce. Its most iconic structure was the Templo Mayor, a massive pyramid dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli (the god of war and the sun) and Tlaloc (the god of rain and agriculture). The Templo Mayor served as the focal point for religious ceremonies and was a symbol of the empire’s power and devotion to its deities.

Beyond its monumental architecture, Tenochtitlán was also known for its bustling marketplaces, such as the grand Tlatelolco market, where goods from across the empire were traded. Items like cacao, jade, obsidian, feathers, textiles, and exotic foods were exchanged, reflecting the empire’s vast economic reach. The city’s complex infrastructure, including its aqueducts, chinampas (floating gardens), and sewage systems, demonstrated the Aztecs’ advanced understanding of agriculture, engineering, and urban management.

(Society and Social Structure)

The Aztec social hierarchy was rigidly structured, with a clear division between the nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin). At the top of the social pyramid was the emperor, known as the huey tlatoani, who wielded absolute power and was considered semi-divine. Below him were the nobles, who held positions as priests, military leaders, and government officials, while the commoners made up the majority of the population, working as farmers, artisans, and laborers.

Education was highly valued, with separate schools for the children of nobles and commoners. The calmecac was the school for the noble youth, where they were trained in leadership, military tactics, and religious practices. Meanwhile, the telpochcalli served the commoner children, focusing on vocational training and basic military instruction. The importance of military service was emphasized throughout Aztec society, as it was both a means of social mobility and a way to acquire captives for religious sacrifices.

(Religion and Cosmology)

Religion was the cornerstone of Aztec life, deeply intertwined with every aspect of their society. The Aztecs were polytheistic, worshiping a vast pantheon of gods, each associated with different elements of nature and human activities. The most important deities included Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun; Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent and god of wind and wisdom; and Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility. The Aztecs believed that their gods required regular offerings to maintain balance in the cosmos, and these offerings often included human sacrifices.

Human sacrifice, though horrifying to European observers, was viewed by the Aztecs as a sacred duty. They believed that the sun needed nourishment in the form of human hearts to continue its journey across the sky, ensuring the survival of the world. Victims, often captured warriors from enemy tribes, were honored as offerings to the gods, and their sacrifice was believed to ensure the continuation of life itself. These rituals were typically performed atop the Templo Mayor, where priests would remove the hearts of the captives as a gift to the gods.

(Cultural Achievements and Legacy)

The Aztecs were not only fierce warriors and devout followers of their gods but also skilled artisans, poets, and mathematicians. They developed a calendar system based on a 365-day agricultural cycle and a 260-day ritual cycle, which governed religious festivals and agricultural activities. The Aztec written language, consisting of pictographs and ideograms, was used to record everything from tribute lists to epic poetry and historical events.

Aztec art and craftsmanship were highly esteemed, with intricate gold and silver jewelry, feather work, and obsidian blades among the most prized creations. They were also known for their music and dance, which were integral parts of religious ceremonies and celebrations.

The Aztec Empire, with its rich culture, military might, and advanced societal structure, was at the height of its power when the Spanish arrived in 1519. The empire’s achievements and contributions to human civilization remain a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the Aztec people, even as the conquest brought an end to their dominance and initiated a new chapter in the history of the Americas.

The Arrival of Hernán Cortés

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire began in 1519 with the arrival of Hernán Cortés, a Spanish conquistador whose ambition and cunning would reshape the course of history in the Americas. Cortés, who had previously served in the Caribbean under the leadership of Diego Velázquez, governor of Cuba, was initially tasked with a reconnaissance mission to explore the coast of Mexico. However, driven by the promise of unimaginable wealth, fame, and a desire to conquer new lands, Cortés defied orders and embarked on a bold and unauthorized expedition into the heart of the Aztec Empire.

(The Expedition: Small Forces, Big Ambitions)

Cortés landed on the eastern coast of what is now Mexico, near present-day Veracruz, with a small but determined force of approximately 600 men, 16 horses, several cannons, and a few hundred indigenous allies from the Yucatán Peninsula who had joined him during his earlier campaigns. Despite the modest size of his army, Cortés’s leadership, strategic thinking, and ruthless determination made him a formidable opponent.

From the moment he set foot on Mexican soil, Cortés demonstrated his resolve to conquer. One of his most symbolic and decisive actions was the scuttling of his ships, an irreversible move that ensured his men had no option but to follow him into the unknown or face certain death. This act solidified his leadership and committed his forces to the mission ahead, leaving no possibility of retreat.

(Early Encounters and Diplomacy)

Cortés quickly established a settlement at Veracruz, which served as both a base of operations and a means of asserting Spanish authority. From this foothold, he began his march inland, determined to reach the fabled city of Tenochtitlán, the heart of the Aztec Empire. Along the way, Cortés encountered various indigenous groups, some of whom were hostile, while others were more receptive to the possibility of an alliance against the powerful Aztecs.

One of the most significant early encounters was with the Tlaxcalans, a fierce and independent people who had long resisted Aztec dominance. The initial meeting between Cortés and the Tlaxcalans was fraught with tension and violence. The Tlaxcalans, wary of the Spanish and their strange weapons, engaged in a series of skirmishes with Cortés’s forces. However, after witnessing the Spaniards’ military prowess, including their use of firearms, steel weapons, and horses—animals previously unknown in the Americas—the Tlaxcalans reconsidered their stance.

Recognizing the potential of the Spanish as powerful allies, the Tlaxcalans eventually chose to join forces with Cortés, seeing an opportunity to overthrow their common enemy, the Aztecs. This alliance proved to be one of the most critical factors in the Spanish conquest. The Tlaxcalans provided Cortés with thousands of warriors, supplies, and crucial knowledge of the local terrain and political landscape, which would prove invaluable in the battles to come.

(Cortés’s Strategic Diplomacy)

Cortés’s ability to forge alliances with indigenous groups discontented with Aztec rule was a testament to his diplomatic skills and understanding of the complex socio-political dynamics of Mesoamerica. He was adept at exploiting the divisions and rivalries among the various city-states and tribes that had been subjugated by the Aztecs. By presenting himself as a liberator rather than a conqueror, Cortés was able to gain the support of key indigenous allies who were essential in his campaign against the Aztec Empire.

In addition to his alliances with the Tlaxcalans, Cortés also skillfully navigated relationships with other indigenous leaders. For example, he negotiated with the Totonacs of Cempoala, who, like the Tlaxcalans, were eager to throw off Aztec rule. These alliances not only bolstered Cortés’s forces but also provided him with valuable intelligence on the strengths and weaknesses of the Aztec Empire.

Cortés’s diplomatic acumen was further demonstrated in his interactions with emissaries from Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor. Moctezuma, informed of the Spaniards’ approach, sent gifts of gold and other treasures to Cortés, perhaps in an attempt to appease or deter him. However, these gifts only served to fuel Cortés’s ambitions and convinced him that even greater wealth awaited him in Tenochtitlán.

Cortés used these gifts strategically, distributing them among his men to ensure their loyalty and further motivating them to continue the march toward the Aztec capital. At the same time, he sent messages to Moctezuma, portraying himself as a peaceful ambassador of the Spanish king while carefully positioning himself for the eventual confrontation.

(The Path to Tenochtitlán)

As Cortés and his growing army moved closer to Tenochtitlán, the tension and anticipation mounted. The journey was fraught with challenges, including difficult terrain, the need to maintain fragile alliances, and the ever-present threat of betrayal. Nevertheless, Cortés’s resolve never wavered, and his ability to inspire and lead his men through adversity kept the expedition on course.

The arrival of Cortés in the Valley of Mexico marked the beginning of the final and most dramatic phase of the conquest. With a mix of indigenous allies and Spanish soldiers, Cortés stood on the brink of an encounter that would change the course of history. His entry into Tenochtitlán, initially peaceful and marked by a cautious welcome from Moctezuma, would soon give way to a series of events that would lead to the fall of the Aztec Empire and the rise of Spanish dominion in the Americas.

The March to Tenochtitlán

Cortés’s march to Tenochtitlán was a journey fraught with challenges, marked by a series of battles, delicate diplomatic maneuvers, and strategic alliances. This journey not only demonstrated Cortés’s military prowess but also his ability to navigate the complex political landscape of Mesoamerica. As the conquistador and his men ventured deeper into the heart of the Aztec Empire, they encountered a mosaic of indigenous cultures, each with its own grievances against Aztec rule. These encounters provided Cortés with valuable intelligence, enabling him to exploit the internal divisions and dissatisfaction among the Aztec Empire’s subject peoples.

(Gathering Allies and Intelligence)

As Cortés advanced toward Tenochtitlán, his forces grew stronger, bolstered by the addition of thousands of indigenous warriors from groups that had long chafed under Aztec domination. The Tlaxcalans, in particular, became one of Cortés’s most important allies. After their initial resistance, the Tlaxcalans recognized the strategic advantage of aligning with the Spanish to overthrow their mutual enemy, the Aztecs. Their deep knowledge of the local terrain, military tactics, and Aztec weaknesses proved invaluable to Cortés.

In addition to military support, these alliances provided Cortés with crucial intelligence about the political dynamics within the Aztec Empire. The Aztecs, under Emperor Moctezuma II, ruled over a vast and diverse population, many of whom were resentful of the heavy tribute demands and harsh treatment they received from their overlords. Cortés skillfully used this resentment to his advantage, portraying himself as a liberator who would free these peoples from Aztec tyranny.

The march to Tenochtitlán also involved numerous diplomatic encounters. Cortés often presented himself as a representative of a powerful foreign king, using this image to awe and intimidate local leaders. He carefully navigated these interactions, offering gifts and assurances of friendship while always keeping his ultimate goal—the conquest of Tenochtitlán—in sight.

(The Approach to Tenochtitlán)

As Cortés and his forces approached Tenochtitlán, the tension grew palpable. The Spaniards were entering the heart of one of the most powerful empires in the world, and the outcome of their journey was far from certain. Moctezuma II, the Aztec emperor, was well aware of the Spaniards’ approach. Reports of the strange, bearded men with their horses and firearms had reached him, and he was deeply troubled by the omens that seemed to foretell the end of his reign.

According to some accounts, Moctezuma may have believed that Cortés was the embodiment of the god Quetzalcoatl, a deity who, according to Aztec prophecy, was destined to return from the east. This belief might have influenced Moctezuma’s initial decision to welcome Cortés into Tenochtitlán rather than confront him with force. However, it is also possible that Moctezuma was attempting to buy time, hoping to better understand the Spaniards’ intentions and capabilities before taking decisive action.

On November 8, 1519, Cortés and his army finally entered Tenochtitlán. The city, built on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco and connected to the mainland by a series of causeways, was a breathtaking sight. Tenochtitlán was one of the largest and most splendid cities in the world, with towering pyramids, elaborate palaces, and vibrant marketplaces. Cortés and his men were astounded by the scale and sophistication of the city, which far exceeded anything they had encountered before in the Americas.

(Moctezuma’s Welcome and the Fragile Peace)

Upon their arrival, Cortés and his men were greeted by Moctezuma II, who, despite his unease, welcomed the Spaniards with great ceremony. The emperor provided lavish accommodations for Cortés and his entourage, and there was an initial period of peaceful coexistence. Moctezuma showered Cortés with gifts, including gold and precious stones, perhaps in an effort to appease the Spaniards or to keep them under his control. The Spanish, however, interpreted these gifts as a sign of submission, further fueling their ambitions.

Despite the outward appearance of cordiality, the situation was precarious. The Spanish were vastly outnumbered and deep within the heart of the Aztec Empire, reliant on the goodwill of their hosts and their indigenous allies. Cortés, aware of the delicate nature of his position, initially took a cautious approach, attempting to maintain the semblance of friendship while quietly consolidating his power.

However, the underlying tensions between the two sides could not be suppressed for long. The Spanish were driven by a relentless desire for wealth and power, and they quickly began to assert their dominance. Cortés took Moctezuma hostage, hoping to use him as a puppet ruler through whom he could control the empire. This act of treachery shocked the Aztecs and strained the fragile peace that had been established.

(The Breaking Point: The Massacre at the Templo Mayor)

The situation reached a breaking point in the spring of 1520, during the festival of Tóxcatl, a religious ceremony held in honor of the god Huitzilopochtli. The festival, which took place at the Templo Mayor, involved elaborate rituals, music, and dancing. While the Aztecs were engaged in these sacred ceremonies, the Spanish, fearing that the gathering could turn into an uprising, launched a surprise attack. Cortés was not present at the time, having left the city to confront a Spanish expedition sent to arrest him for insubordination. In his absence, his deputy, Pedro de Alvarado, ordered the massacre of the unarmed Aztec nobles and priests who were participating in the festival.

This brutal and unprovoked attack sparked a full-scale uprising against the Spanish. The Aztecs, enraged by the massacre, took up arms and laid siege to the Spaniards, trapping them within the palace where they were quartered. The once-welcoming city of Tenochtitlán was now a hostile and dangerous environment for the Spanish, who found themselves under constant attack.

(The Road to Disaster: La Noche Triste)

The situation rapidly deteriorated for Cortés and his men. When Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán after dealing with the Spanish expedition, he found the city in chaos. The Aztecs had turned against him, and even Moctezuma, who had been a captive, could no longer control his people. In a desperate attempt to quell the rebellion, Moctezuma was brought before his people to appeal for peace, but he was met with scorn and was struck by stones thrown by his own subjects. Moctezuma would later die from his injuries or possibly at the hands of the Spanish.

Realizing that they could no longer hold Tenochtitlán, Cortés and his forces attempted a night escape from the city on June 30, 1520, an event that would become known as La Noche Triste (The Night of Sorrows). As they tried to flee across the causeways, the Spanish and their allies were ambushed by Aztec warriors. In the chaos that ensued, many Spaniards and indigenous allies were killed, and much of the treasure they had accumulated was lost to the waters of Lake Texcoco. Cortés himself narrowly escaped with his life.

Despite this devastating setback, Cortés regrouped and, with the support of his indigenous allies, would eventually return to lay siege to Tenochtitlán, leading to the final conquest of the city in 1521. The march to Tenochtitlán, with its mixture of diplomacy, treachery, and violence, set the stage for one of the most dramatic and tragic episodes in the history of the Americas, forever altering the fate of the Aztec Empire and the continent.

The Siege of Tenochtitlán

The siege of Tenochtitlán, which took place from May to August 1521, was a cataclysmic event that marked the end of the Aztec Empire and the beginning of Spanish dominion over much of Mesoamerica. This brutal and drawn-out conflict was not only a military engagement but also a humanitarian disaster, characterized by intense fighting, starvation, disease, and immense suffering on both sides.

(Strategic Preparations and Initial Attacks)

After the retreat following La Noche Triste, Hernán Cortés regrouped his forces and devised a meticulous plan to conquer Tenochtitlán. Recognizing the city’s formidable defenses and the difficulty of a direct assault, Cortés focused on isolating the city and cutting off its essential supplies. He built a fleet of brigantines—small warships that could navigate the shallow waters of Lake Texcoco—using timber and supplies brought from the Gulf Coast. These ships were crucial in gaining control of the lake, allowing the Spanish to launch attacks from multiple directions and to sever the city’s supply lines.

Cortés also secured the loyalty of a vast network of indigenous allies, particularly the Tlaxcalans, who had long harbored animosity towards the Aztecs. The combined Spanish-indigenous force swelled to tens of thousands of warriors, all motivated by the prospect of dismantling the Aztec hegemony. The Spanish forces were equipped with advanced weaponry, including cannons, crossbows, and steel swords, while their indigenous allies brought overwhelming numbers and intimate knowledge of the local terrain.

The siege began in earnest with a series of coordinated attacks on the causeways leading into Tenochtitlán. The Spanish and their allies captured these vital routes, effectively cutting off the city from the mainland. The brigantines patrolled the lake, preventing supplies from reaching the besieged population and allowing the Spanish to bombard the city from the water. This strategy gradually wore down the Aztecs, who, despite their fierce resistance, found themselves increasingly isolated and vulnerable.

(The Aztec Resistance and the Ravages of Disease)

The Aztecs, led by their new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, who had taken power after the death of Moctezuma II, mounted a determined defense of their capital. They fought with unparalleled courage, using every resource at their disposal to repel the invaders. The city’s defenders engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat, constructed makeshift fortifications, and launched counterattacks to reclaim lost territory. Despite the overwhelming odds, the Aztecs’ resolve remained unbroken, and they inflicted significant casualties on the Spanish and their allies.

However, the Aztecs were fighting a losing battle against an invisible enemy—European diseases like smallpox, which had been introduced to the Americas by the Spanish. These diseases spread rapidly through the densely populated city, decimating the population and weakening the Aztecs’ ability to sustain their defense. Smallpox, in particular, took a devastating toll, killing tens of thousands, including many of the city’s leaders and warriors. The epidemic compounded the effects of starvation and deprivation caused by the siege, leading to a humanitarian catastrophe within the city walls.

(The Final Assault and the Fall of Tenochtitlán)

As the siege dragged on, the situation inside Tenochtitlán became increasingly desperate. The city’s inhabitants were reduced to eating anything they could find—dogs, rats, insects, and even grass. The combination of hunger, disease, and constant bombardment eroded the Aztecs’ ability to resist. The Spanish and their allies, sensing victory, intensified their assaults, systematically destroying the city’s buildings and infrastructure.

By August 1521, Tenochtitlán was in ruins, its streets filled with the dead and dying. The final assault came on August 13, when Cuauhtémoc, realizing the hopelessness of the situation, attempted to flee the city in a canoe. He was captured by the Spanish, effectively signaling the end of the Aztec Empire. With Cuauhtémoc’s capture, the remaining Aztec forces surrendered, and the once-great city of Tenochtitlán fell into Spanish hands.

The conquest of Tenochtitlán marked a turning point in the history of the Americas. The fall of the city not only signaled the end of the Aztec Empire but also the beginning of Spanish colonial rule over large parts of the Americas. The destruction of Tenochtitlán was so thorough that little of the original city remains today. On its ruins, the Spanish built Mexico City, which would become the capital of New Spain and a major center of Spanish colonial power.

(Aftermath and Legacy)

The aftermath of the siege was devastating for the indigenous peoples of the region. The population of the Valley of Mexico, once numbering in the millions, was decimated by war, disease, and forced labor under Spanish rule. The social, cultural, and religious structures that had defined Aztec civilization were systematically dismantled by the Spanish, who imposed their language, religion, and institutions on the conquered peoples.

The fall of Tenochtitlán also set a precedent for the Spanish conquest of other parts of the Americas. The tactics used by Cortés—strategic alliances, the exploitation of indigenous rivalries, and the ruthless application of military force—would be replicated by other conquistadors in their campaigns to subdue the vast territories that would become the Spanish Empire.

Today, the siege of Tenochtitlán is remembered as a pivotal moment in history, a clash of civilizations that reshaped the world. The story of the Aztecs’ heroic resistance, the catastrophic impact of European diseases, and the subsequent transformation of the Americas continues to resonate, offering lessons on the complexities of cultural encounters, the consequences of imperialism, and the resilience of indigenous peoples in the face of overwhelming odds.

Conclusion,

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521 was a watershed moment that set the stage for a new era of European dominance in the Americas. The dramatic fall of Tenochtitlán, a city of remarkable sophistication and power, not only marked the end of the Aztec Empire but also initiated a transformative period of colonization. The Spanish victory brought with it a wave of change that would dramatically alter the continent’s socio-political and cultural landscape. This conquest was not merely a military achievement but a profound cultural upheaval that laid the groundwork for centuries of Spanish influence and control in the region.

As the Spanish established their presence, the Americas underwent a complex process of transformation, characterized by a blend of conflict, adaptation, and exchange. The interaction between European settlers and indigenous peoples led to significant cultural and societal shifts, as well as the emergence of new hybrid identities and practices. The legacy of the Spanish conquest is a multifaceted one, reflecting both the achievements and the challenges of this transformative period. This epoch, marked by its blend of confrontation and convergence, set the stage for the diverse and dynamic history of the Americas that followed.