The Rwandan Genocide stands as one of the most harrowing and tragic episodes in recent human history, a brutal conflict that unfolded over just 100 days in 1994. Within this brief yet devastating period, an estimated 800,000 people were systematically slaughtered, leaving deep scars on the nation and its people. This atrocity was marked by extreme violence and hatred, fueled by longstanding ethnic tensions between the Hutu majority and the Tutsi minority. The genocide not only decimated a significant portion of Rwanda’s population but also exposed the catastrophic failures of international intervention and the dark potential of unchecked ethnic division.

As the world watched in silence, the genocide unfolded with alarming efficiency and cruelty. The methods employed in the killings, the role of propaganda in inciting violence, and the severe inadequacies of the international response are critical aspects that underscore the gravity of this tragic event. Understanding the Rwandan Genocide involves not only recognizing the immediate impact of the violence but also reflecting on the broader implications for global intervention, justice, and reconciliation. This article delves into the historical and ethnic context that set the stage for the genocide, examines the brutal execution of the violence, and explores the subsequent efforts for recovery and reconciliation in the aftermath of one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century.

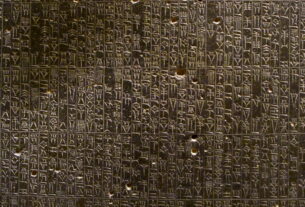

(flickr.com)

Historical and Ethnic Context

(Ethnic Composition and Historical Hierarchies)

Rwanda’s ethnic landscape has been shaped by centuries of social and political evolution involving its three primary groups: the Hutu, the Tutsi, and the Twa. Historically, the Tutsi minority held a higher status, often occupying roles of leadership and authority over the Hutu majority. This hierarchical structure was reinforced by traditional systems that placed the Tutsi in positions of economic and social power, which was perceived as both legitimate and natural by those within the system. The Twa, a smaller group with distinct cultural practices, were generally marginalized and had limited social influence compared to the Hutu and Tutsi.

The pre-colonial power dynamics were significantly altered during the colonial era. European powers, particularly Belgium, exploited and exacerbated existing ethnic divisions by favoring the Tutsi minority. The Belgian administration implemented policies that entrenched the Tutsi’s privileged status, which included assigning them administrative and military roles, thus deepening the ethnic divide. This favoritism created a lasting legacy of tension and resentment among the Hutu, setting the stage for future conflicts and instability in Rwandan society.

(Colonial Impact and Power Shifts)

The Belgian colonial period had a profound impact on Rwanda’s ethnic relations, as the colonizers’ favoritism towards the Tutsi contributed to the creation of a rigid ethnic hierarchy. The Belgians issued identity cards that classified individuals by ethnicity, which further entrenched the divide and institutionalized the Tutsi dominance. This system of preferential treatment for the Tutsi sowed seeds of discord and resentment among the Hutu majority, who were subjected to political and economic disenfranchisement.

The end of Belgian rule in the early 1960s marked a significant shift in Rwanda’s political dynamics. As the country moved towards independence, power transitioned to the Hutu majority, leading to a reversal of the previously dominant Tutsi status. The new Hutu-led government enacted policies that marginalized the Tutsi population, fostering an environment of ethnic rivalry and systemic violence. This period of power transition, characterized by violent clashes and political upheaval, laid the foundation for the intense ethnic conflict that would later culminate in the Rwandan Genocide.

(Post-Colonial Changes and Rising Tensions)

Following independence, Rwanda experienced a series of political shifts that exacerbated ethnic tensions. The Hutu-led government, now in control, undertook measures to assert dominance over the Tutsi population, resulting in widespread discrimination and violence. This shift was marked by violent purges and political repression against those perceived as Tutsi sympathizers or adversaries, creating a climate of fear and mistrust within Rwandan society. The Hutu majority’s efforts to consolidate power often involved violent reprisals and punitive measures against the Tutsi community.

By the early 1990s, the political landscape was highly volatile, with ongoing ethnic grievances simmering beneath the surface. The rise of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), composed largely of Tutsi exiles who had fled the country during earlier periods of violence, further intensified the conflict. The RPF’s military campaign against the Hutu-led government was driven by long-standing frustrations and a quest for political and social justice. This conflict, marked by increasing hostilities and political instability, set the stage for the eruption of violence that would become the Rwandan Genocide.

(Emergence of the Rwandan Patriotic Front)

The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) emerged in the early 1990s as a key player in Rwanda’s ethnic conflict. Composed primarily of Tutsi exiles who had fled to neighboring countries during previous waves of violence, the RPF aimed to overthrow the Hutu-led government and address the historical grievances of the Tutsi population. The RPF’s goal was to establish a more inclusive political system that would rectify the injustices and inequalities perpetuated by the Hutu-dominated regime. Their military and political activities sought to challenge the entrenched power structures and advocate for the rights of the marginalized Tutsi community.

The RPF’s actions were met with increasing hostility from the Hutu government, which perceived the RPF as a significant threat to its power and stability. The escalating conflict between the RPF and the Hutu government was marked by a series of violent clashes and skirmishes, further deepening the ethnic divide. The RPF’s efforts to gain control were accompanied by widespread propaganda and inflammatory rhetoric from the Hutu government, which sought to rally support by portraying the RPF as a dangerous enemy and inciting fear and hatred among the Hutu population.

(The Assassination of President Habyarimana and the Genocide)

On April 6, 1994, the assassination of President Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, served as the immediate catalyst for the Rwandan Genocide. The plane carrying Habyarimana was shot down under mysterious circumstances, and the incident was quickly blamed on the Tutsi and their allies. This event acted as a trigger for the extremist factions within the Hutu government to launch a coordinated campaign of mass murder against the Tutsi population. The government used the assassination as a pretext to mobilize and incite violence, leading to a rapid and widespread campaign of genocide.

The genocide unfolded with chilling efficiency and brutality. Over the course of just 100 days, an estimated 800,000 people were killed, including Tutsis and moderate Hutus who opposed the violence. The genocide was characterized by its speed and scale, with extremists using propaganda and fear to mobilize ordinary citizens to participate in the violence. The rapid and systematic nature of the killings, along with the lack of effective intervention from the international community, allowed the genocide to continue unchecked until the RPF’s military victory in July 1994 brought an end to the mass atrocities.

The Genocide Unfolds

(Systematic and Widespread Brutality)

The Rwandan Genocide commenced with an unprecedented wave of brutality and violence that was both systematic and widespread. The extremist Hutu militias, particularly the Interahamwe, along with government forces, orchestrated a coordinated campaign of mass murder against the Tutsi population and moderate Hutus who opposed the extremist agenda. The genocide was marked by its alarming speed and efficiency, as the perpetrators implemented a meticulously planned strategy to eliminate their targets. Over the course of just three months, the violence escalated rapidly, with roadblocks and checkpoints set up across the country to identify and apprehend victims.

The mass killings were carried out in various locations, including homes, schools, churches, and other public places. The genocide’s brutality was evident in the manner in which civilians were targeted and slaughtered. The use of machetes, small arms, and other weapons led to a high number of gruesome and violent deaths. The perpetrators employed a methodical approach to ensure that the killings were as effective as possible, often using lists of names and addresses to locate their victims.

(Role of Propaganda and Public Participation)

The role of propaganda was crucial in fueling and sustaining the genocide. The Hutu extremists utilized state-controlled media to disseminate hate-filled broadcasts and printed materials that dehumanized the Tutsi and incited violence. Radio stations, such as Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), played a significant role in spreading propaganda, using inflammatory rhetoric to demonize the Tutsi and encourage ordinary Hutu citizens to participate in the violence. The broadcasts included false claims and inflammatory messages that painted the Tutsi as enemies and threats to the Hutu community.

This propaganda had a profound impact on the public’s perception and actions, turning ordinary citizens into perpetrators of violence. Many Hutus, previously uninvolved in political violence, were coerced or persuaded to join the killings. The combination of propaganda and fear created an environment where participation in the genocide was often seen as a patriotic duty or a means of self-preservation. As a result, the genocide was not only a top-down atrocity orchestrated by extremist leaders but also a widespread and deeply entrenched form of communal violence that involved significant public participation.

International Response and Intervention

(Criticism of Inadequate International Response)

The international response to the Rwandan Genocide has been widely criticized for its glaring inadequacy and failure to prevent or stop the atrocities. Despite the mounting evidence of mass killings and widespread violence, the international community, including key institutions like the United Nations and major world powers, exhibited a disturbing reluctance to take decisive action. The United Nations had a peacekeeping force, the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), deployed in the country at the onset of the genocide. However, UNAMIR was severely under-resourced and hampered by a restrictive mandate that limited its ability to intervene effectively. The peacekeepers were primarily tasked with monitoring and facilitating the implementation of the Arusha Accords, which had aimed to bring peace but were quickly overshadowed by the outbreak of violence.

The lack of a robust and timely international response allowed the genocide to proceed unchecked. International actors, including influential countries and organizations, were slow to recognize the scale and severity of the crisis. Political considerations, bureaucratic inertia, and a general reluctance to become involved in what was perceived as an internal conflict contributed to the failure to mount an effective intervention. This inaction led to a protracted period of violence and mass murder, with the international community’s responses being limited to statements of condemnation rather than concrete actions to halt the genocide.

(Missed Opportunities and Lessons Learned)

In retrospect, there were numerous missed opportunities for early intervention and prevention that could have mitigated the scale of the genocide. The international community had access to early warning signs, including credible reports of planned violence and escalating hate propaganda, but failed to act on them with urgency. The UN and its member states were criticized for their inability to respond proactively to these indicators, which included intelligence reports and appeals from humanitarian organizations on the ground.

The international community’s failure to take decisive action during critical moments is seen as a significant factor in the magnitude of the tragedy. The genocide finally came to an end only with the military victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in July 1994, which marked the collapse of the genocidal government and the establishment of a new regime. The aftermath of the genocide prompted a reassessment of international policies and practices related to conflict prevention and humanitarian intervention. The Rwandan Genocide highlighted the urgent need for reforms in international response mechanisms, including improved early warning systems, more robust peacekeeping mandates, and a stronger commitment to preventing and addressing mass atrocities.

Aftermath and Reconciliation

(Rebuilding a Ravaged Nation)

The aftermath of the Rwandan Genocide left the country in profound disarray, with an estimated 800,000 people dead and countless others displaced and deeply traumatized. The genocide’s impact extended beyond the immediate loss of life, leaving communities shattered and the nation’s infrastructure in ruins. The scale of the destruction posed an enormous challenge for Rwanda as it sought to rebuild and heal from the immense loss and suffering. The task of reconstruction was not only about physical rebuilding but also about addressing the psychological and social wounds inflicted by the genocide.

The Rwandan government, led by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), faced the daunting task of restoring order and stability in a country rife with ethnic divisions and mutual distrust. The RPF’s leadership prioritized efforts to reestablish governance and public services, and to address the needs of both survivors and perpetrators. This included addressing the pervasive issues of poverty and unemployment, which were exacerbated by the genocide and contributed to ongoing instability.

(Justice and Reconciliation Efforts)

One of the most significant post-genocide initiatives was the implementation of the Gacaca court system, a traditional form of community-based justice. The Gacaca courts were designed to handle the overwhelming number of genocide-related cases and to provide a forum for justice that was both inclusive and community-oriented. These courts aimed to facilitate truth-telling and accountability while fostering a process of communal healing. By involving local communities in the judicial process, the Gacaca system sought to address the extensive backlog of cases and to restore a sense of justice and reconciliation at the grassroots level.

In addition to the Gacaca courts, the Rwandan government embarked on a broader program of national reconciliation and unity. Efforts included promoting national cohesion through educational reforms, public commemoration events, and reconciliation programs designed to bridge ethnic divides. The government also focused on economic development as a means of fostering stability and improving the quality of life for all Rwandans. The country has made notable strides in economic growth and social cohesion since the genocide, transforming into one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies. However, the legacy of the genocide continues to cast a long shadow over Rwanda’s society. Ongoing efforts to address the needs of survivors, support reconciliation, and prevent the recurrence of such atrocities remain critical to the nation’s long-term stability and healing.

The Rwandan Genocide remains an indelible mark on the collective conscience of humanity, a stark reminder of the depths of cruelty that can emerge from ethnic hatred and political extremism. The genocide’s swift and devastating impact, characterized by systematic violence and widespread participation, highlighted the severe consequences of unchecked hatred and the profound failure of the international community to intervene effectively. In the wake of this tragedy, Rwanda’s efforts towards justice and reconciliation have been both a testament to the resilience of its people and a crucial step towards healing a nation scarred by unimaginable loss.

The genocide not only transformed Rwanda but also served as a sobering lesson for global governance and humanitarian intervention. The international community’s delayed response and the subsequent attempts to address the failures of the past underscore the need for a more proactive and decisive approach in preventing such atrocities. As Rwanda continues to recover and rebuild, the legacy of the genocide remains a powerful call to action for the world to uphold the principles of human dignity, justice, and unity, ensuring that the horrors of the past are never repeated.